The Agreement with Alfort, not only a nice project, but also necessary

– The Agreement with Alfort, not only a nice project, but also necessary

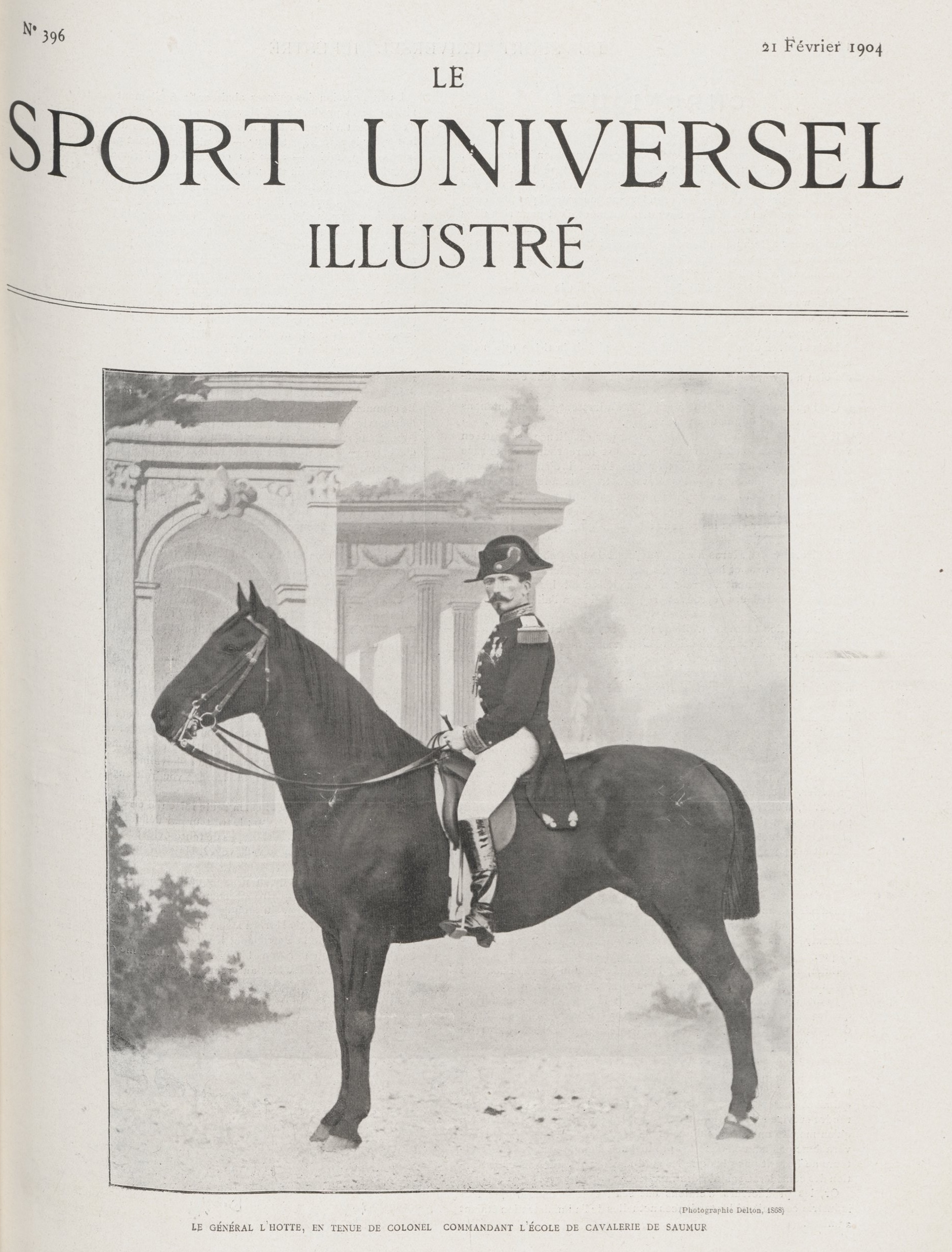

The World Horse Library, after the National Library of France, the IFCE, and the Deauville Media Library, closed the 2019 financial year with the signing of an agreement with the National Veterinary School of Alfort, which manages the funds distributed among the different schools of the veterinary art in France. The Director of the Alfort School, Christophe Degueurce , has worked hard on the inventories, referencing and numbering of these collections. This professor of horse medicine, author of a large number of works on this subject and on the evolution of veterinary medicine, was first in charge of the Fragonard Museum and is now, at the age of fifty-three, Director of the National Veterinary School at Maisons-Alfort. He was happy to answer our questions.

X. L.: Tell us about the partnership signed in December 2019 between Alfort and the World Horse Library…. How did the idea come about? What is the objective? What is your idea?

C.D. The partnership between the former veterinary school of Alfort, created in 1766 in Paris, and the World Horse Library is a natural and logical one, as the school has an important heritage of rare and precious books largely, but not exclusively, dedicated to the horse. However, the horse represents the vast majority of historical veterinary publications at least until the 1930s.

So when we heard about the existence of the World Horse Library it seemed obvious to us that we should approach it; the aim of this agreement is that the Veterinary School participates in the process of information and digitization of works devoted to the horse, particularly in the part related to all scientific disciplines linked to the horse, to its medicine, and also to the breeding part.

The idea is to become the bridge to other veterinary schools, more or less as it was done with the Inter-University Health Library in Paris.

X. L.: What kind of collection are we talking about, who has the physical possession?

C.D. We consider that the veterinary schools of Alfort and Lyon have complementary collections that give a global and detailed overview of what has been published in French on the subject. This global fund shared between Lyon and Alfort illustrates the anatomy, physiology, medicine, surgery of the horse and has a beautiful collection on its breeding, as I mentioned above.

X. L.: In this French collection, what part corresponds to horse medicine?

C.D.: It is the major part.

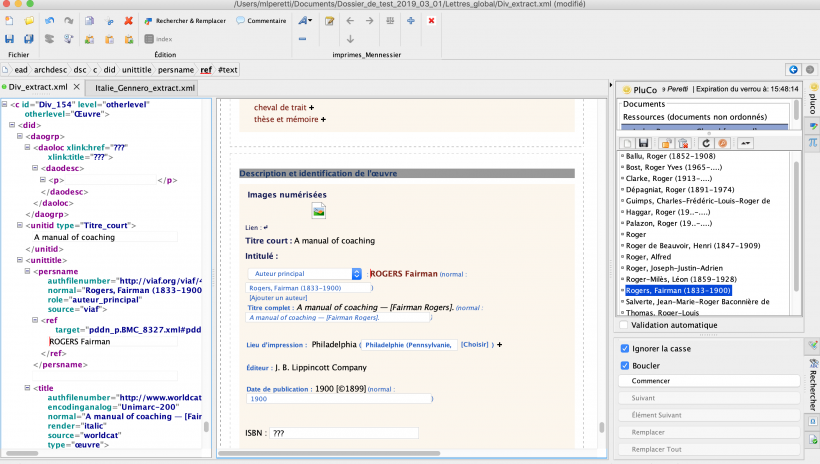

X. L.: How is it distributed? Geographically, thematically, physically (manuscripts, books, theses, pamphlets, articles), how much of it is digitized?

C.D.: We have a few dozen important old manuscripts, but the ones that have been digitized by Gallica and are now available online are mainly theses, pamphlets and much more recent periodicals.

All of these will be indexed in the World Horse Library.

The part of digital documents today is not insignificant and is of high quality. The major periodicals are digital. As are many works from the 18th and 19th centuries and the challenge now is to consolidate the digitized collection.

Rather, we are working on the edges of a hard core. For example, we need to complete the collection with the proceedings of the scientific societies of rural veterinary surgeons; in Normandy, the Orne, the Manche, the Eure, there were important scientific societies that stimulated competition through the publication of newspapers and journals that have not yet been digitized. The same is true of the sources testifying to the treatment of the horse in military disciplines, which are still scarce and quite important.

X. L. Who will decide and be in charge of the “supply” to the World Horse Library, in what order, with what logic?

C. D.: A committee chaired by Mrs. Brigitte Laude, Director of the Library of the Veterinary School of Alfort, accompanied by her teams, especially Virginie Willaime and myself as Director of the School, and as organizer of the digitization processes with BiuSante and Gallica for several decades.

X. L.: Could you give an “outline” of the evolution of the veterinary art of the horse and its diffusion through the works that have been dedicated to it over the centuries?

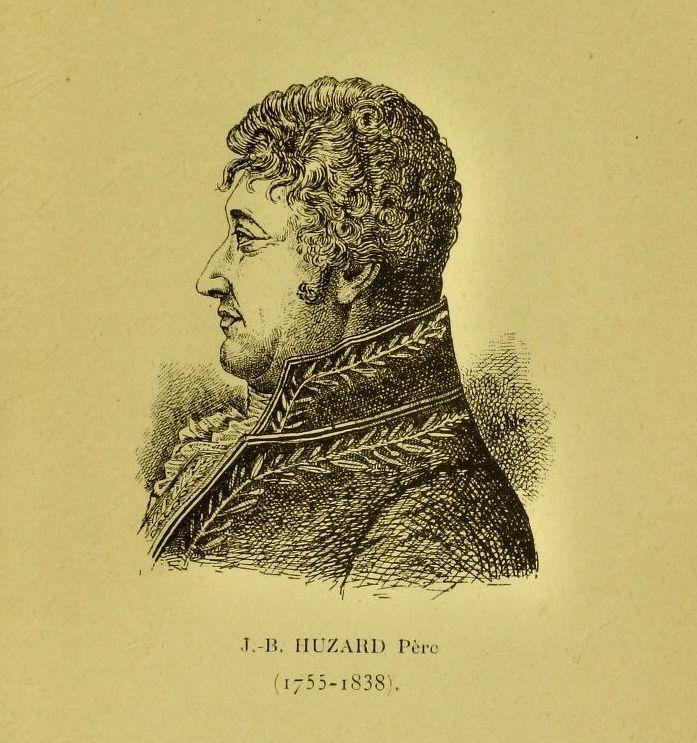

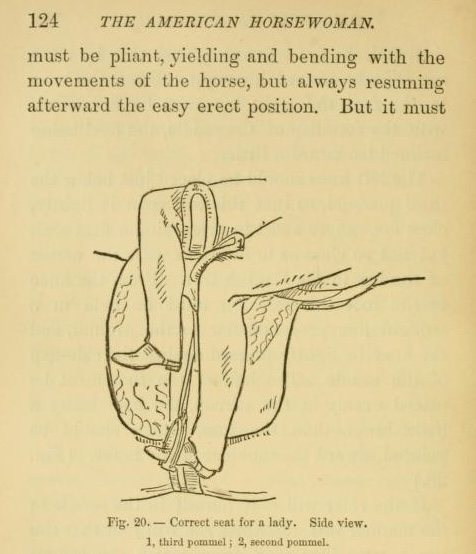

C. D.: From the most remote antiquity to about the 18th century, the veterinary art has been as static as human medicine. There were three great consecutive revolutions. The first, with a new approach to the anatomy of the horse, took place in the middle of the 16th century, similar to what happened in human medical disciplines. The Renaissance was a period when things were rationalized and great treatises on the anatomy of the horse were published, illustrating its constitution. This was the first break with the ancient writings; the dogma inherited from antiquity came to an end. The second major stage of the 18th century, which was purely institutional, corresponded to the creation of veterinary schools. Although these institutions changed almost nothing in horse medicine and surgery, they opened the way for new professionals. The third revolution was technical, chemical, pharmaceutical and methodological. This was at the end of the 19th century. Vaccination, the creation of active principles derived from chemical synthesis, the industrial production of new materials projected veterinary medicine into a new dynamic.

X. L.: The current situation and any concerns related to the “digital era”?

C.D.: As the subject we are interested in is bibliography, it is becoming more and more digital and less and less physical, which gives rise to a great anxiety about “what will be left of our era in the times to come?”

We know how to preserve physical volumes. Preserving digital archives is something new and it is not easy to calculate how long this intangible heritage will last.

I think that the ambition to safeguard digital data is a challenge for the World Horse Library.

X. L. What are the rarities, the treasures of the Alfort Library in general?

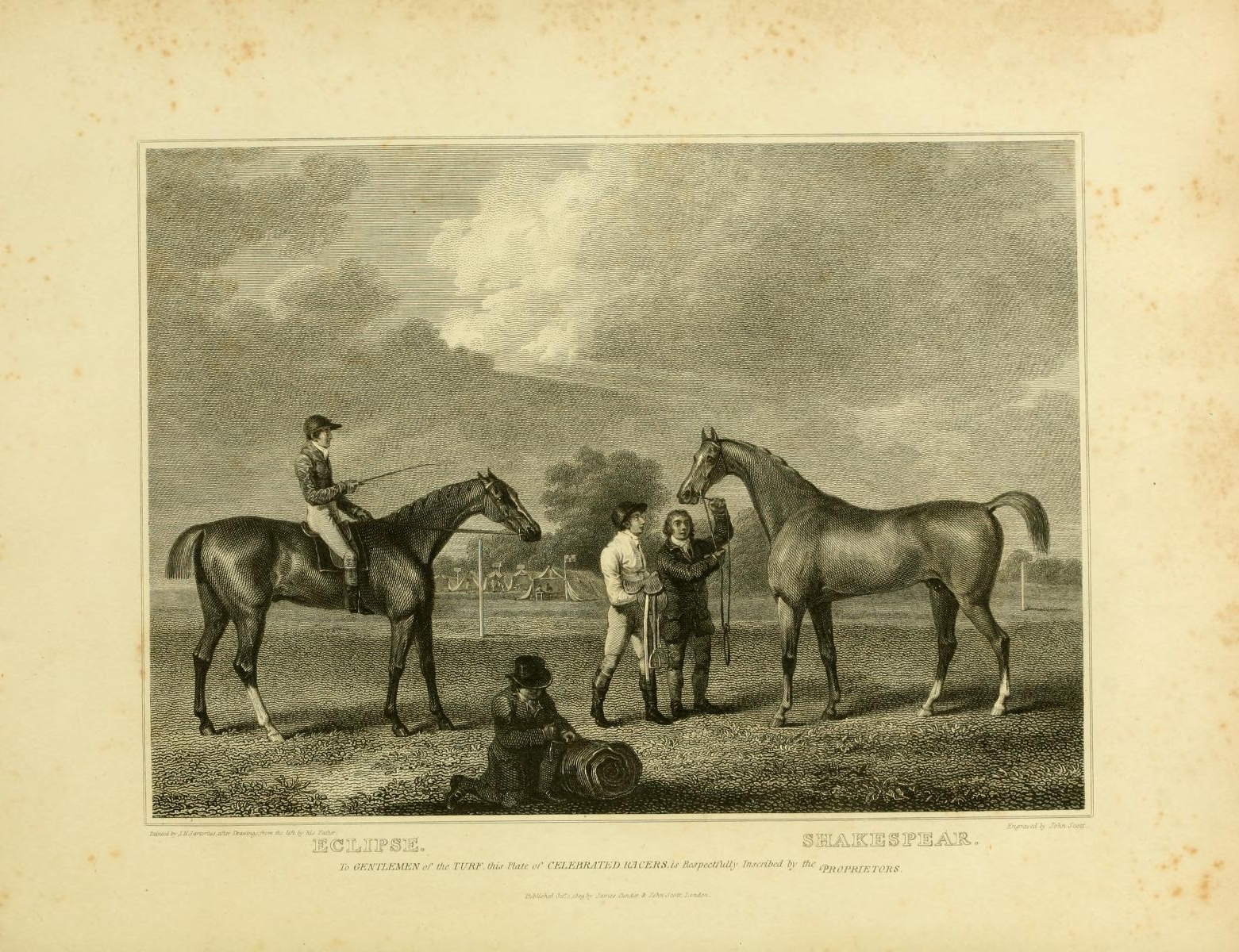

C.D.: There are several, such as the incunabula Mesnagier de Paris of 1492, the treatises of the 16th century, what we call hippiatrica , such as the collections of treatment methods that reproduced the prescriptions of the horse doctors of the Eastern Roman Empire. And then of course the great classics such as Le cours d’hippiatrique by Philippe-Étienne Lafosse of 1772, those of Saunier, of Newcastle… they are all very beautiful.

X. L.: Do you yourself have a personal taste for old books? About horses? Are you a collector?

C.D.: Yes, I love old books, but I am not a collector. I have a library at home, I have bought a lot of books, but in material terms they are of poor quality. I buy them for the content. I focus on them more as a historian than as a collector.

X. L.: And on the book side, as a bibliophile or bibliomaniac?

C. D.: Well, clearly: bibliophile and not bibliomaniac.

X. L.: In that case, a little tour of your library…

C. D.: You will mainly find scientific journals, such as the great journals of the profession, the great works that marked the knowledge and development of veterinary medicine and especially the dictionaries of the 19th century, which are like bibles that we can still refer to today.

But also some older works that were a success story of ancient horse medicine.

X. L. Do you ride horses? Have you ever ridden a horse?

C.D.: I rode a lot but I don’t ride any more. I had a horse for twenty-eight years. I come from the countryside. The horse imposed itself on me almost as a means of locomotion. I had an inseparable relationship with the horse, not for the competition or any expert horsemanship, but for the pleasure of going through the forest with him. ….

X. L.: Nowadays?

C. D.: No, I don’t really have anything more to say about my relationship with horses. I’d say that’s outdated!

X. L.: Does that explain why you chose to become a veterinarian?

C. D.: Definitely, but more generally because of my love for animals and nature. I really wanted to be a farmer, but life took me in a different direction. Then I wanted to be a blacksmith, and then veterinarian…. That’s how it happened: through the dance of doubt.

X. L.: Tell us about your professional career. Studies, practice, teaching.

C. D.: I was a good student at high school and higher education was within my reach. I graduated in 1990 in Alfort. I worked outside school for some time and then embarked on a career as a teacher-researcher. I went through the stages, starting with research, a DEA and then a thesis on the biomechanics of the horse. In 1993, as a professor of anatomy, I was asked to take over the direction of the Fragonard Museum. And then, each year became more demanding, more exciting, until in 2017 I agreed to take over the direction of the Alfort Veterinary School.

X. L. To conclude, do you think – and please forgive my optimism – that the practice, the existence of the horse, will make sense for future generations, in our increasingly urban, digital and virtual societies beyond libraries?

In that context, what roles can libraries eventually play?

C. D.: I believe that the horse will remain a permanent and unique link with nature. That was for me and there is no reason for it to change in the future.

The big issue is the growing urbanization. Cities are becoming more and more sprawling. The distance between the city and the place where horses can be brought to live – because I don’t believe in the idea of installing horses in ultra urban terrain, especially in Paris – will be a brake on their practice mainly in the “horse nature” dimension, the one I was passionate about.

In conclusion, the World Horse Library, a digital repertory of human production and a vast reservoir of knowledge on the subject, is an attractive but above all necessary project in which the National Veterinary School of Alfort should be involved.

Interview by Xavier Libbrecht