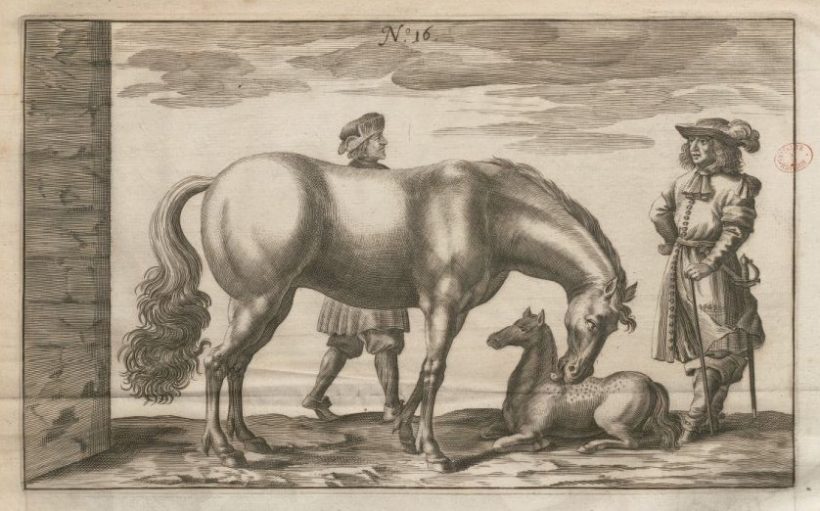

Nicolas Blondeau, with his head and hands on the horse

Nicolas Blondeau passed away suddenly on January 22, 2026. This great horseman, whose equestrian science placed paramount importance on culture, had repeatedly expressed his deep passion for the development of the World Horse Library. We share in the grief of his loved ones and wish to pay him a final tribute through this insightful interview about his life, published in 2020.

“Humanity believes it can live without animals by urbanizing societies and delegating intelligence to digital systems. If this were to happen, human societies would be inhuman.” This is what we will remember from the long interview that the professional horseman Nicolas Blondeau, founder and leader of a horse training method and of a company that applies it in Saumur, agreed to give us.

An original trajectory that at first glance seems to be made by groping, but for the young sexagenarian who has his head and hands on the horse every day, it turns out to be more solid than it seems because…. it’s all about sensitivity!

Blondeau’s quest for an ideal confronted with reality, a quest based on knowledge learned from illustrious authors and predecessors, nourished by the fruit of experience, which he understands as “culture”?

One certainty beyond these questions, these confessions: the fierce desire to transmit by and for the horse.

Therefore, Nicolas Blondeau’s meeting with the World Library of the Horse in the spring of 2020 is not a coincidence.

X. L.: Tell us about your early days on horseback, about that passion.

N.B.: In 1967, my father was finishing his job as a surgeon at the hospital in Ruffec (Charente), and it was thanks to him that I discovered horses.

Passionate about sailing and boats, he told us at that time “Children, the sea is gone, there is no more tide. I want to have an old grey horse!”.

And the following week we had in the house seven horses, they were neither old nor gray.

I was eleven years old, my father sixty-two. He said that as a child he had ridden horses a few times at the Jesuits.

With François, my brother two years older than me, who entered the Haras du Pin School a year later, we took our first steps, almost always alone, with the colts bred in the house and especially with the Connemara ponies, imported from Ireland by René-Louis Chagnaud, my father’s neighbor and friend and creator of the French stud book.

I remember in particular a certain Island Earl who would become the head of the breed we know today.

It was in Charente that we met Xavier des Roches de Chassay and Jean Pelissier. In retrospect, I recognize that these first encounters with horsemen were invaluable! From that moment on and thanks to them, I never thought about anything else but horses again.

X. L.: What is your student and professional background?

N.B.: My father had an original concept about children’s education.

He liked to criticize the French system that “locks pupils in classrooms instead of motivating them outdoors”. I easily agreed with this opinion and rode horses a lot.

Apart from horses, I liked to draw. At the age of sixteen I entered to study interior architecture at the private school in Poitiers, the Bugeant Academy. The program consisted of three years of studies, the first year I did it with a lot of interest, the second year with a little less attendance because the horses took more and more of my time.

At the beginning of the third year, I traveled to La Rochelle; I informed my father that I was suspending my “studies” to devote myself fully to riding. I received no reproach from him, only encouragement: “The luck we have in life is the encounters we make, the important thing is to love them”.

I think I admired my father even more that day.

The only “studies” that I can rely on, was my time at the Bugeant Academy, which allowed me to meet Christian Philippe, a very fashionable decorator in Paris in the seventies. He came down to Poitiers every two weeks to give us lessons. I remember he openly lamented the general level of the students and the declining mood they showed, but with him “I was popular”, he knew I rode horses because I kept talking about it. “At least you have a passion for something,” he would say.

That favorable treatment was enough for me to be invited in 1974 to the opening of the trendy discotheque in Paris, L’Aventure, which was inaugurated by the singer Dany on Avenue Victor Hugo.

There you have my student tour….

At the end of my military service in 1976, I lost my mother as her youngest son, and entered the service of Colonel des Roches de Chassay as an intern in horse breeding.

According to Fombelle who always “punctuated” his compliments, this former rider of the international show jumping team, a specialist in “small” speed tests, had the means to carry out his policies. He had created on his Greigueuil property a training center for jumping horses, which remained his passion.

Horses, stables, arena, covered riding arena, everything was perfectly cared for and maintained. The motto of that house could have been “Love for horses, rigor and respect”.

In 1977 I entered the competition as a gentleman rider under the light blue coat with maroon stripes, light blue sleeves and maroon helmet.

That same year I bought a beautiful refurbished thoroughbred that I rode outside of service hours and later dedicated to the “rectangles” of dressage. At that time I resumed contact with General Champvallier.

At the beginning of 1978, I left the Charente to set up a competition stable in the Vendée, where, unfortunately, there were more horses than horse owners who paid the pension… but it was nevertheless a time full of wonderful memories, such as competition rides, dressage, all-round competitions, fox hunts in the Parc Soubise with the “Bodard”, seven hours a day riding, being in a short time World Champion in the three disciplines, with the same horse! Something never seen before! …This dream life would end with a one-week practice in Saumur with four horses and a squire for each of them: Patrick Le Rolland, Dominique Flament, Alain François and Alain Franqueville… (No more, no less!)

I learned a lot that week.

“La Vendée is la dolce vita”. But, despite all efforts, my mother’s heritage reached its limits. In the spring of 1980 I “went up to Paris” after paying with difficulty all the overdue bills. I stopped only to have breakfast with my friend Bonneau in Maintenons, to pet Tancarville (the horse with which Michel Parot had set in 1974 the French record for the high jump at 2.41 meters, NDLR).

On April 1, 1980, without a diploma but thanks to a favorable graphology analysis, I started working at the Hemmerlé Firm, experts in the insurance companies sector.

Hemmerlé was one of the most important insurance companies in Paris. Directed by Gérard Hemmerlé, a charismatic “centralien” (engineer from the Ecole Centrale de Paris), Lorraine, author of works on “business losses” which were a reference in the field.

An anecdote: shortly after I started in the profession, I met other collaborators in the office of the “boss” to whom I asked about their “background”: “And what is your Blondeau training?”

Shyly and a little embarrassed I answered : “Sir, I have been very much involved with horses”.

Gérard Hemmerlé’s answer in front of the general astonishment was: “It’s not the best training but that can’t hurt!”

Oddly enough, I eventually struck up a sincere friendship with this man with whom I had nothing in common. It is undoubtedly one of the most important encounters of my life.

I “made a career” for twenty-five years and thanks to this activity as an expert in insurance companies, I was able to organize and divide my time between Paris and the countryside, thus responding to my passion.

In the eighties, I settled my horses in Poitou after a season of competitions in the Paris region. At that time, I regularly went to Limoges to work with Commander Bernard de Fombelle. We also met at competitions and I have lasting memories of this contact.

Fombelle is still the man and rider who has had the greatest impact on my life.

At the end of 1990, I returned to Saumur and approached General Pierre Durand.

Fombelle said of “Colonel” Durand: “He is “a little” my pupil!”

Retired from business, the General had left the ENE and on Thursdays he came to give courses to wealthy landowners at the Paris Polo Club. We often met and returned together to Saumur.

The journey became as short as the animated discussions.

Durand was the one who allowed me to “understand” Fombelle, to make the link.

They are probably the ones who taught me the most, many others also helped me.

Despite not having their level, both knew how to accept me and take an interest in my work. I had a real affection for these two men even though many things separated us.

X. L.: And this return to the horse – why, how, what for?

N.B.: I had the “click” in the mid-nineties.

It always bothered me, in terms of training, that rupture of the state of mind between the horse’s training and the rest of his training.

The incoherence between the way of approaching the foals, of imposing oneself on their backs by applying the principles decreed by our French riding tradition. I chose to devote a large part of my life to horse training out of respect for the elderly and above all out of equestrian logic.

Very early on I realized that the main and only obstacle for the horse to overcome its relationship with man was the fear of man.

In 1995 the “method” was codified after a few years of hesitation, and in 2003 it was published by Belin.

I then decided to suspend my Parisian activity to devote myself to the teaching of this method and to the work with horses.

On May 20, 2005 the Blondeau School opened its doors…. At the gates of the ENE.

X. L.: At what point of your project are you at the moment?

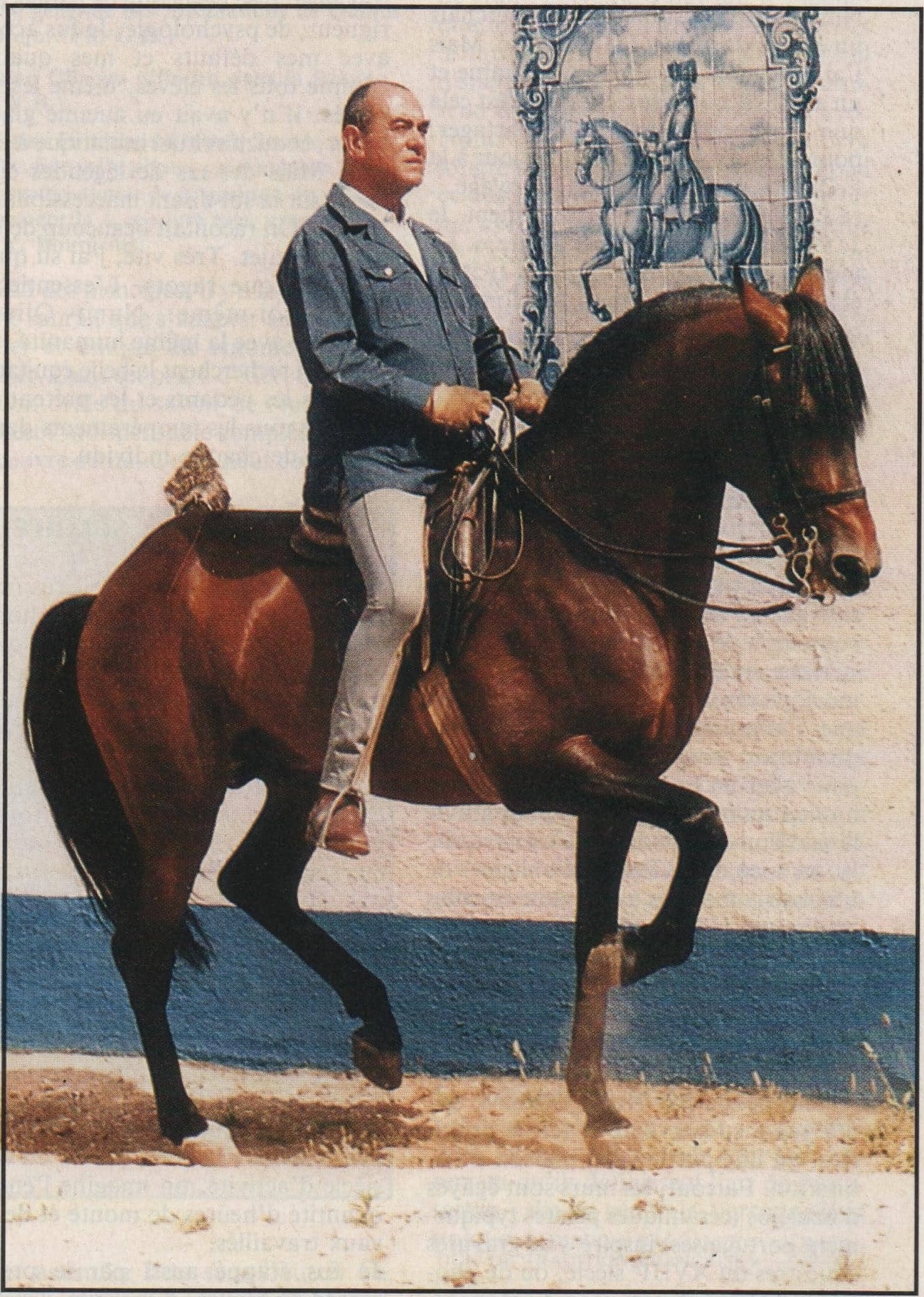

N.B.: Thanks mainly to the racing world, after ten years of activity, the foals that have been educated at the school have passed their tests very quickly, gradually implementing the Blondeau method that still continues to impose itself.

General Pierre Durand said one day to my wife Florence “If you don’t count on the “policies”, you won’t get anywhere in France”.

The President of the Region, Hervé Morin, proposed to us in 2015 to install the Blondeau School in Normandy.

We were proposed the Haras du Pin and then the CIRALE, in Goustranville.

The Blondeau Institute will open in 2023 in Dozulé (14).

In 2016, the first CHEVALEDUC program led by Jocelyne Porcher was born thanks to the support of the Normandy region and partnership with INRA. It is aimed at learning about the impact of horse training on their future career. The Blondeau Institute integrates three activities: the education of horses, the training of students and the research center in partnership with INRA and the Normandy Region.

X. L.: Can you explain why the Blondeau School, which has now become the “Blondeau Institute”, is original and unique?

N. B.: What is original is the crossing of experiences and knowledge between the professionals in charge of the horses, the apprentices and the researchers. This way of pedagogy, based on interactions, takes away the sacredness of the scientific word and puts empirical knowledge on the same level, and also allows everyone to nourish their practices with those of others. Professionals get used to take the time to think about their practices and researchers to integrate in their research protocol the real work situation and thus to get out of their laboratories. For me, the winners are both the students and the horses.

X. L.: Your first readings on the horse: books, magazines, authors? How did they influence you in your decision to create the “Blondeau School”? Can we evoke the culture in relation to it? Are these readings still useful, still alive in the teaching of horsemanship in general? If so, how do you divide them between your daily work and teaching?

N. B.: The Blondeau method taught at the school is based on the principles of the French riding tradition.

These principles are applied from the beginning of the young horse’s education.

In this way the equestrian culture becomes alive in the education of horses as well as in the instruction of humans.

General L’Hotte wrote: “The art is not in the books that only instruct those who already know”. So we can only understand what we have experienced. Which leads to guiding students by telling them to “reinvent” horsemanship.

In my opinion, outdoor riding can contribute, through the practice of racehorse training, the venery or the complete competition, the sit for acrobatics, the disciplines of polo or horse-ball, to the application of the principles of the Comte d’Aure, which imposes the use of horses “in their dimensions”, while favoring balance on horseback, an essential quality of any rider.

X. L.: Your teachers in the field?

N. B.: Baucher’s contribution to equestrian sport, especially in show jumping, as well as in pure dressage, is considerable.

The current show jumping competition was already wonderfully defined by Colonel Margot as “an institute at 40 per hour!”

General L’Hotte, by the explanation and promulgation of these principles, and later André Jousseaume, by their application in sport riding, each made their contribution.

Dr. Pradier, with his research on equestrian mechanics, as well as Dr. Giniaux, echoed by Jean-Claude Racinet, also contributed to “making the link”, enriching our culture.

In conclusion, General Durand spoke of a “measured Baucherism grafted on a classical trunk”.

X. L.: Do you like old books?

N. B.: Of course I love old books and I am lucky enough to have been offered some good books of which some have not been reprinted. Sometimes old works have the advantage of being noticed by their first reader. For example, the work Journal de dressage in which the author Fillis provokes Saint-Phalle, the owner of the book wrote in pencil “Monsieur de Saint Phalle a gagné son pari!” (“Monsieur de Saint Phalle won his bet”). In the 19th century, culture was alive!

X. L.: Bibliophile or bibliomaniac?

N. B.: In that sense I would be perhaps more of a bibliophile than a bibliomaniac?

X. L.: A small tour of your library…. quantity, quality…

N. B.: I must have more or less five hundred books. Undoubtedly my favorite author is General L’Hotte, his two works are always on my desk or on my night table, and I always reread them…

Équitation Académique by Général Decarpentry remains a reference among those books. It was one of the first I tried to assimilate (I had to read it several times).

I loved Comprendre l’équitation by Jean Saint-Fort-Paillard.

In my opinion, the work of historian Marion Scali lives up to the person she was. Her Baucher, among others, made us discover an unknown man; Marion was a real journalist who also helped me a lot…

I recently read Équitation impertinente by my friend Vedrenne. I found the content true to its title, with insightful observations and sympathetic criticism.

X. L.: You yourself wrote and published in the Belin editions:

-Le débourrage par la méthode Blondeau (2004).

-In retrospect, what do you think of these two books today?

N. B.: The two books on the Blondeau method published by Belin describe the procedures and the progression of the method; they are more like “user manuals”.

X. L.: So the third one will be different?

N.B. : I hope that the next book will be more complete, that it will deal with the state of mind with which horses should be treated, that state of mind of the rider. It should also integrate the first results of the research program started with INRA.

X. L.: State of mind…. Culture?

N. B.: It is important that all this is lived and transmitted. It is necessary to make the culture live, to understand it to make it evolve.

It is what Jaurès advised, “We do not teach what we know or what we think we know, we only teach and can teach what we are”.

The method evolves like culture, thanks to work and research, which will be the subject of a work entitled Les humanités du cheval .

X. L.: What can we say about the current situation of specialized publishing, its quality, what we can expect, its future?

N. B. : No comment.

X. L.: What do you think about our era of “digital transition”?

N. B. : The digitization of works of equestrian literature is a very important research tool at the level of the World Library of the Horse, for future research on the history of horsemanship. For example, digitization makes it possible to work on the vocabulary used and opens up new research on the semantics of horsemanship.

On the other hand, the arrival of different applications that claim to replace the eye of the rider is a risk if these applications are used as an objectification of something that is not the experience of the body, the intelligence of the experience. We run the risk of having riders glued to their smartphones who forget the importance of this patient and affective observation of the horses, which is the only way to know and understand them.

X. L.: Since you mention it, more precisely, what is the role of the World Horse Library, what do you expect as a professional?

N. B.: The World Equestrian Library has a fundamental role: that of preserving our roots, the specificity of our horsemanship. French horsemanship cannot grow, develop, and flourish, if it does not preserve its origins.

Young riders do not know the richness of our equestrian culture. It is important that they have access to it with the tools of their time.

X. L.: Finally, do you think – and please forgive my optimism – that the practice, the existence of the horse, will make sense for future generations, in our increasingly urban, digital and virtual societies beyond libraries?

In that context, what roles can libraries eventually have?

N. B.: There are no human societies in the world without animals. Horses, like other animals, remind us in every interaction that Homo sapiens is an integral part of the world of the living and that our species has no future, no possible existence, outside the world of the living. Humanity believes it can live without animals by urbanizing societies and delegating intelligence to digital systems. If this were to happen, human societies would be inhuman.

What horses teach humans is the language of the body and how to evolve in the world of the senses, of emotions, and that is why we need horses.

Interview by Xavier Libbrecht