The reception of the book Art équestre, by Xenophon

How did Xenophon’s book “Art équestre ” come down to us? What was its influence on the writers who have dealt with this subject, and particularly on the Renaissance squires, most of them being Italian?

This is probably the most interesting part for us, bibliophiles, historians, collectors and others curious about the equestrian theme, of the whole of the colloquium that Alexandre Blaineau hosted at Hermès on December 04 in Paris, accompanied by Jeremy Clément (Hellenist), François Vallat (Veterinarian), Jean-Pierre Tuloup (Horseman) and Jean-Louis Gouraud (Editor).

As we shall see, Alexandre Blaineau is not completely closed, even if…. We will risk settling for “no smoke without fire”, as the popular saying goes, not to say vulgar proverb of which the first traces can be found in the 14th century. X. L.

Contrary to other works by Xenophon, the Art équestre was very rarely quoted during Antiquity, except on a few occasions by Diogenes Laertius or by doctors who dealt with horses in Late Antiquity [1].

Does this mean that there was a certain lack of interest in these works, which are after all rather austere and rather intended for specialists? One has to be careful with such a blunt opinion about how little influence these texts had: the true recognition of these writings cannot be measured by the yardstick of a literature that only partially reached us. However, to claim that there was a continuum of Xenophon’s thought on equestrian matters throughout antiquity would, on the contrary, be completely false. Indeed, whether written down or not [2], there have been innumerable equestrian experiences in all places and periods. Without exaggerating, we can think that Art équestre was preserved largely because its author was famous and highly valued for his style: had Xenophon been a bad writer, the text would have quickly disappeared.

First of all, what happened to Art équestre in European culture between the 16th and 18th centuries?

1. Art équestre in European equestrian culture (16th – 18th centuries)

1.1. Editions and translations of Art équestre

Art équestre was more widely published than Hipparque : some twenty codices of the first treatise exist, compared with four of the treatise on the Officer of Chivalry [3]. However, the interest in the latter may have been earlier. In fact, the chamberlain of Pope Eugene IV, Lapus Castelliunculus, published in 1437 the first Latin translation of the work, which he entitled Praefectus equitum. Lapus mentions in his preface elements that refer directly to the content of the equestrian treatise (care, horsemanship and military exercises), so he must have had knowledge of the Art équestre.

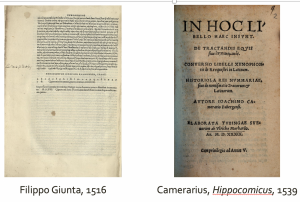

T he first edition of Xenophon’s complete works, which includes the text of the Art équestre, appeared in 1516 in Florence, and was published at the request of Filippo Giunta, founder of a great dynasty of Italian printers [4]. Some time later, the great German scholar Camerarius (1500-1574), author of a Hippocomicus [5] and also a lover of horses [6], made a Latin translation of the Art équestre [7]. Other notable editions of Xenophon’s works were published in Europe during the 16th century [8]. Evangelista Ortense [9] was the first to translate it into Italian, and Marc’Antonio Gandini did the same with the two equestrian treatises, in a volume dated 1588, in which he mentioned that the writings of this “ eccellentissimo ” philosopher and historian were particularly useful for men of war [10]. However, translations of the treatise into languages other than Italian are rare. In Spain only Diego Gracián de Alderete (c. 1500 – c. 1584) [11] translated Xenophon’s works from Greek into Spanish, including De equitandi Ratione (On the Military Art of Chivalry) [12].

F ew editions and translations of the treatise are to be found in 17th century Europe. The first attempt at a French translation, in 1613, was made by Pyramus de Candolle, an important typographer of the time, who published his Œuvres de Xénophon [13] that was not without errors [14]. In Italy, Francesco Liberati, author of a great equestrian treatise, added to it a translation of the text in his own language [15]. Also worth mentioning in England is the work of Henrici Aldrich (1647-1710), theologian and musician, dean of the University of Oxford, who brought together in 1693, in a single volume, in a bilingual version (Greek and Latin) [16], the three technical treatises (Art équestre, Hipparque, and Art de la Chasse). In 1703, the geographer Edward Wells (1667-1727) proposed a Latin translation of Xenophon’s works [17].

In the 18th century, a double movement on the translation of the treatise can be observed. After Francesco Liberati, equestrian experts integrated into their own equestrian treatises the text of Xenophon translated into their own languages.

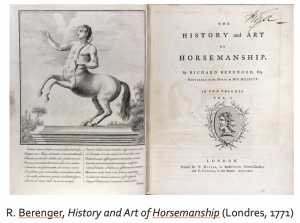

This is the case in England of R. Berenger, author of History and Art of Horsemanship (London, 1771). Xenophon’s book is respectable for him, not only because of its antiquity and because it is the only one to have survived the ravages of time, but also because its recommendations are still valid [18]. Berenger includes some comments in the notes, sometimes relying on ancient references, such as those of Pollux or Hesychios, of the Greek horse doctors (especially Apsyrtos), of Virgil, and also of the French veterinarian Bourgelat [19].

Dupaty de Clam acts as translator in France [20]. However, he is not faithful to the Greek text, and the writer does not include grounds or annotations in the translation. For him, it is only a flower that adorns the beginning of his work, as he explains in his preface: “I precede my mechanical demonstrations [21] with a translation of Xenophon’s book on Chivalry; a work that has not yet been translated into French [which is false] [22], which will please horsemen and distract them from the attention required by the rest of the work” (p. VI). This version of Art équestre contains a large number of translation errors.

A second movement is more in line with the philological tradition. Zeunius published a book on Xenophon’s political and technical treatises, supplemented by Arrien’s Art de la chasse [23]. In 1794, Jean-Baptiste Gail had also published a volume with translations of the Traité d’Equitation et le Maître de la Cavalerie [24]. As a scrupulous Hellenist and professor at the Collège de France, he made an honest and serious presentation of the texts, inserting the French text opposite the Greek text. Gail relied on several manuscripts available in French libraries and at the end of his book he provides critical foundations [25]. He has also read the work of Dupaty de Clam, and does not fail to quote a few sentences from this “excellent squire, but who knew little Greek” [26]. However, his work also contains errors and allows himself “beautiful infidences” which he more or less justifies in his notes. Finally, at the beginning of the 19th century, Benjamin Weiske carried out a philological research on the Art équestre and the Hipparque, accompanying the Greek text with extensive commentaries in Latin [27]. This was one of the first consistent works, showing a concern for the careful elaboration of the text.

Parallel to these translation works, the Peri Hippikês was a source in the construction of the knowledge of horse veterinary medicine in the 16th-18th centuries.

1.2. Xenophon and the tradition of equine veterinary medicine

The chain of knowledge of equine veterinary medicine, which includes Xenophon’s description of the anatomy of the good horse and his observations on equine husbandry, began in antiquity through compilers such as Magon, Diophanes or Cassius Dionysius of Utica, as well as Latin agronomists (Varron and Columella), and later the authors of the collection of equine veterinary medicine. (CHG)

In the 15th century, Leon Battista Alberti cites Xenophon among numerous Greek and Latin authors, ancient and medieval, most of them horse veterinarians or agronomists, in his De equo animante, which deals with the anatomy, breeding, training and diseases of horses [28]. The question is to what extent did Xenophon’s text influence Alberti.

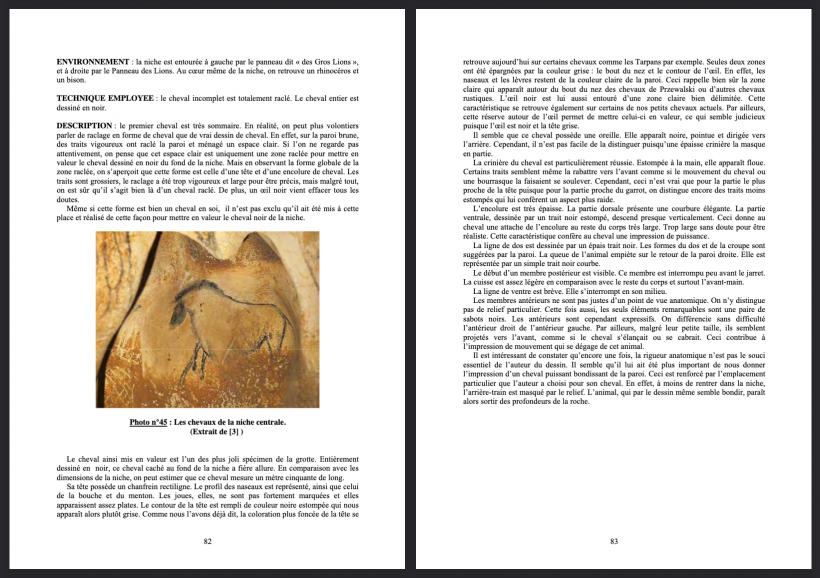

Alberti had Xenophon’s writing before his eyes: for example, concerning the pasterns, Xenophon recommends that they should not be too straight like those of a goat (hosper aigos) (I, 4), which Alberti takes up on his own (“Internodia quae ad pedes insident, non directa ad perpendiculum (uti sunt caprarum)”) [29]. Alberti’s description of the ideal horse (in particular: the small and slender head, the bulging eyes, the dilated nostrils, the straight and slender neck, the swollen belly, the muscles of the legs adapted to the efforts, the hard hooves) really brings to mind that of Cimon and Xenophon, but it seems to me that these are aesthetic and functional canons that we find in the other authors he cites. We also find similar anatomical descriptions in Varron, Columella, Anatolius, Palladius, Virgil, Calpurnius, Nemesius and Oppianus [30].

In 1551, the Zurich scholar Conrad Gesner published the first part of a very detailed compendium on nature, Historiae animalium, which presents the different species, including horses (De equo) [31]. Gesner relies on Xenophon’s text, and when he refers to the various anatomical notions he sometimes quotes the Greek text.

The physician of King Francis the First, Jean Ruel (1474-1537), dedicated to his majesty a collection on horse medicine translated into Latin, composed mainly of Greek authors including Aristotle, Hippocrates, Galen, Cimon of Athens and Xenophon [32]. This ancient knowledge of horse medicine fed the science of horses, which developed from treatises on farriery: for example, the veterinary surgeon Gervase Markham (c. 1568-1637), who wrote several books on animal care, mentions in his Markham’s Masterpiece [33] Xenophon at the top of a list of writers who dealt with the breeding of horses and cattle (including Camerarius). Likewise, Jacques de Solleysel (1617-1680), who published in 1664 Le Parfait Maréchal, in which he refers mainly to equine medicine, had noted Xenophon’s interest in horses: in addition to the Hippiatriques, he had read the two equestrian treatises [34].

From the 16th to the beginning of the 18th century, the ancient discourse continues to influence the veterinary knowledge under construction. Daniel Roche writes that, in addition, “a more rational empiricism of observation developed immediately, that of the professionals, squires, specialists in horse medicine and farriers of the great European cavalries [who] built up a new body of knowledge based on practices [35] “. In this context, Claude Bourgelat, founder of the veterinary schools in France, strongly criticised the Athenian author, who, in his opinion, had not understood anything about the anatomy of the horse. Thus, he writes in an inquisitive tone: “Would we think that a man like Xenophon wanted to define the horse’s gait by the height of its heels, its goodwill by the circles of the nail, the goodness of its legs by the sound they emit when they hit the ground, the strength of its limbs by the few veins that will enter its composition, its complexion and temperament by the length of its ears? “Xenophon is not the only one to suffer the wrath of Bourgelat, for no ancient author who dared to take an interest in equids (from Aristotle to Vegetius) found favour in his eyes, because they lived in “dark centuries” [36]. According to him, it is better to turn to the Italian science that has developed since the Renaissance.

Since the 18th century, the development of equine veterinary science gradually separated from an ancestral tradition constituted mainly by the teachings of Xenophon. In contrast, specialists in the equestrian art quickly recognised Xenophon as a master, which can be seen from the Renaissance onwards.

1.3. Equestrian science and equestrian art

In Alberti’s De Equo animante, one can glimpse between its lines the Xenophontic teaching of leading the horse without anger, but with calm and gentleness. However, once again, it is difficult to be certain that this is a reference to the Athenian author: according to Serena Salomone, an Italian Hellenist, Alberti’s philosophical-religious principles, based on his readings of Seneca, Cicero and the Church Fathers, could well explain this form of respect for the animal [37]. Moreover, scholars are divided over the fact that the first authors of equestrian treatises in modern times, such as Federico Grisone [38] or Cesare Fiaschi [39], do not quote Xenophon. Some, for example, agree that Grisone’s work (Gli ordini di cavalcare (1550)), is inspired by Xenophon’s ideas, others doubt it [40]. The advice that the Neapolitan gives on the position of the horseman is reminiscent of that given by Xenophon in chapter VII of his book. However, in very precise cases in which the horse disobeys, Grisone sometimes recommends an abrupt mounting, totally contrary to the advice of the Athenian master [41]. So, although Grisone may have read Xenophon, he also established equestrian rules of his time [42] which came from his own experience and the influence of Spanish horsemanship.

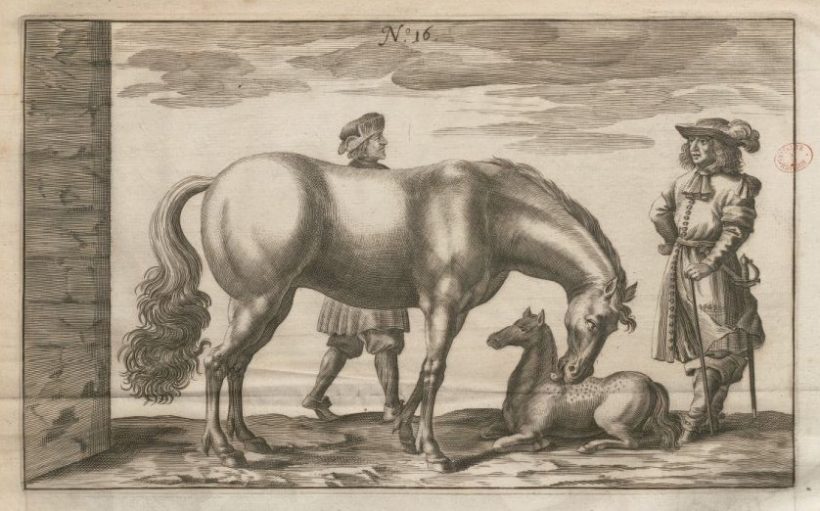

Claudio Corte, author of Il Cavallarizzo (1562) [43] and Pasquale Carraciolo, author of La gloria del cavallo (1566) [44] are much more explicit. Indeed, they cite Xenophon among numerous ancient authors. Corte refers to Xenophon in his prologue as the author who in his two treatises writes the best that exists on horses [45]. Even more, he presents Cimon as the first person to write about the equestrian art, probably based on the first words of the Xenophontic treatise. Carraciolo does the same when he refers to the anecdote of the bronze horse dedicated to Eleusinion in honour of Cimon [46]. When Corte mentions that the stable must be in sight of the master (Book I, chapter XXVI) [47], he is quoting Xenophon. Speaking of the turnings (Book II, chapter II), he mentions that Xenophon evokes them in his treatises many times. In the same book II, chapter XX, he refers to poppusmos, the same term used by the Athenian author to designate the whistle with which the rider communicates with his horse (Art équestre, IX, 10)) [48]. Caracciolo uses the expression jenophontic (kunèpodes) to refer to horses that stand upright on their pasterns (p. 155). An entire chapter of La Gloria del cavallo is devoted to the bridles according to Xenophon (Briglie secondo Senofonte, p. 349-350), another to the discipline imposed on the horse, also according to Xenophonte (Disciplinare un cavallo secondo Senofonte, p. 360-367). The quotations from the Athenian author are very numerous and do not only refer to the equestrian treatise. Both Caracciolo and Corte use a framework of ancient references [49] to illustrate the aristocratic ethics, based on the discipline of the horse and its rider: Xenophon’s teaching reinforces the concept that equestrian practices are one of the symbols of social recognition [50]. These Italian works (Grisone, Corte, Caracciolo) were successfully disseminated in Europe, as were the editions of Grisone in France (we find about ten before 1610): indeed, at that time, the Italian language was the ideal means of communication for cultural transmission [51].

In England, John Astley wrote an Art of Riding (1584) [52]. Related to Queen Elizabeth on his mother’s side, appointed under her reign as “Master and Treasurer of her Majesty’s Jewels and Plate”, he was a Member of Parliament. A specialist in horses, he was appointed Commissioner of War Horses in the county of Middlesex. His treatise is based on the advice of Xenophon and Grisone, especially on the conformation of the horse (chapter 2). Chapters 8 and 9, again drawing on the two authors he appreciates [53], speak of the horse trained for war. Indeed, we can see his inspiration in the Athenian author when he advises rewarding the horse when it does well what is asked of it, and punishing it in the opposite case [54].

One might think that Montaigne, the devourer of ancient texts and famous for conducting “his longest conversations” while riding a horse, would have been one of the first French authors to refer to and comment on Art équestre. But this is not the case. He considers Xenophon as a writer “of great importance” but evokes him mainly because of his adventures recounted in the Anabase, or because he is interested in the Cyropédie. In fact, in his chapter in Essais entitled “ Des Destriers ” (I, 48), he does not comment on the treatise on horsemanship. However, he had in his possession all the works of the Greek author in a compilation of Latin translations made by Catellion and published in Basel in 1551 [55]. On the other hand, he had used Caracciolo’s treatise [56].

In the 15th and 16th centuries, Xenophon appears in equestrian circles as an author whom we rediscover and quote, and from whom we follow some advice. The circulation of his books encouraged the interest he received in England, France and other countries. He is considered as one of the undisputed masters of the equestrian art to be quoted, between humanism and aristocratic values, Xenophon reinforces the characteristic values of horse men [57].

Francesco Liberati, author of La Perfettione del cavallo (1639), refers in the third volume to breeding practices (reproduction, care, feeding, branding). We have already mentioned that in his book he includes a translation of the Xenophontic treatise made by himself [58]. He also had a list of authors on whom he had based his work, including Camerarius, whose work was probably useful to him for the translation of the Art équestre. Pinter von des Au, for his part, wrote in 1664 a work on the training and care of horses [59]. He also referred to a long list of writers including experts in the treatment of horse diseases, both Greek and Latin, such as Cesare Fiaschi, Pasquale Caracciolo and, of course, Xenophon. Some specialists in the study of the horse at the time scoffed at the creation of these lists of authors, which they considered superfluous and useless [60]. In any case, the scholars of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, by writing or translating texts on the study of the horse or equestrian studies, contributed to forging the identity of horsemen, since they drew on a catalogue of practices and values from a more or less distant tradition [61].

Few authors of great equestrian treatises of the 18th century mention Xenophon as one of the first masters of reference. As we have seen, while it is R. Berenger who translated the Art équestre, François Robichon de La Guérinière, for example, does not mention him at all in his École de cavalerie (1733). However, unlike the knowledge of equine veterinary medicine, which seems to have abandoned the ancient tradition, equitation jennophontique continued to arouse the interest of horse scholars in the following centuries.

2. The Squire Xenophon or the future of Art équestre in the 19th and 20th centuries

The rigorous analysis of the Xenophontic text that began at the end of the 18th century continued in the following century. However, the technical nature of the treatise gave birth to two approaches, that of the Hellenists, different from that of the horse scholars: in France, this antagonism is particularly noticeable in the translations of Courier and Curnieu.

2.1 The French example: Hellenists versus horse scholars

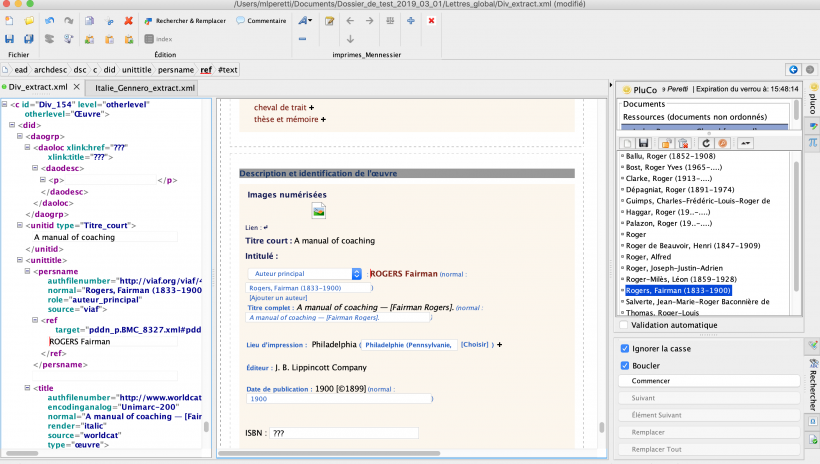

The Frenchman Paul-Louis Courier (1772-1825), a writer, polemicist and horse artilleryman, carried out, at the beginning of the 20th century, a great work of translation of the two equestrian treatises [62]. He used his knowledge of horsemanship [63], but above all, as he was a Hellenist, he was able to understand the texts very precisely [64]. His important work was immediately recognised, as a chronicler of the time remarked: “Until today, this text had never appeared in all its purity; even in the most recognised editions, it had suffered alterations. Wanting to repair the damage caused by his predecessors, the new editor has embarked on a great work, and by collating most of the manuscripts of Italy and France, he has found many lessons that the first editors did not know” [65].

However, Courier’s work was soon questioned: “Courrier’s [sic] translation, although far superior to that of the other two [Dupaty de Clam and Gail’s], suffers from many errors; he substitutes several times his own ideas for those of Xenophon, which are not always correct. His notes prove that Courrier [sic] was no great connoisseur of horses; he knew no more about this subject than the artillery generals who excelled in his time, who, judging by those who survived, must not have been experts in the study of horses. Therefore, it is safe to say that a true translation of the book Peri Ippikês has yet to be made”. This is what we read in an article by Baron de Curnieu [66] on the new translation of Xenophon’s treatise. Curnieu himself is even harsher in his book: “Paul-Louis Courier’s notes suggest that he had little knowledge of horses; moreover, his originality and taste for antiquity alone made him lose his way. He tries to interpret the text more from his ideas, generally very peculiar, than from the natural sense of the text itself” (p. XVIII-XX) [67].

Baron de Curnieu (1811-1871) [68], famous for being a good Hellenist, justified his new translation by the fact that he had found different interpretations, with which he sometimes disagreed, in the readings of the translations of Gail, Dupaty de Clam or Courier. On the other hand, Xenophon’s treatise could replace all the publications on the equestrian art and horse breeding of his time, and still be read and meditated upon (p. XIX-XVI) because he considers it “clear, precise, pleasant in form and detail”. His ambition is not the same as Courier’s: Curnieu presents himself as a “man of the horse” and as such claims the “indulgence” of scholars (p. 155). Mennessier de la Lance, the equestrian bibliographer, considers that “the best translation to consult” is his [69]

The 19th century translations in France, for their part, followed the teachings of Gail, Courier and Curnieu and brought nothing new to the table [70]. In 1950, Edouard Delebecque, a Hellenist and former pupil of the Saumur riding school [71], offered a translation of great quality [72]. Paul Morand, writer and lover of horsemanship, for example, in the bibliography of his Anthologie de la littérature équestre, associates the work of Curnieu and Delebecque (without mentioning that of Courier) [73]. During these two centuries, while French horse specialists continued to be interested in Xenophon’s Art Equestre, Hellenists, for their part, remained relatively discreet about it.

2.2. The acceptance of Art équestre in Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries: miracle or illusion of a continuum?

Relatively few new editions and translations of the treatise appeared in the 19th and 20th centuries [74]. In the equestrian world, however, Xenophon is regarded as one of the first links in a chain of great masters of horsemanship. Count Savary de Lancosme-Brèves (1809-1873) refers to this ancient text as a founding document of Western equestrian science, following Curnieu’s translation: “From this practice Xenophon draws the first equestrian truths which served as the basis of the theoretical school for a long time, and some of which are still in use today” [75].

Thus, according to Albert Monteilhet, this treatise would have inspired the horsemanship of the Romans, the Byzantines, the Italian school of the Renaissance, and then the masters of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries [76]. The Peri Hippikês, according to him, could even have been written by the great French horseman François Baucher [77].

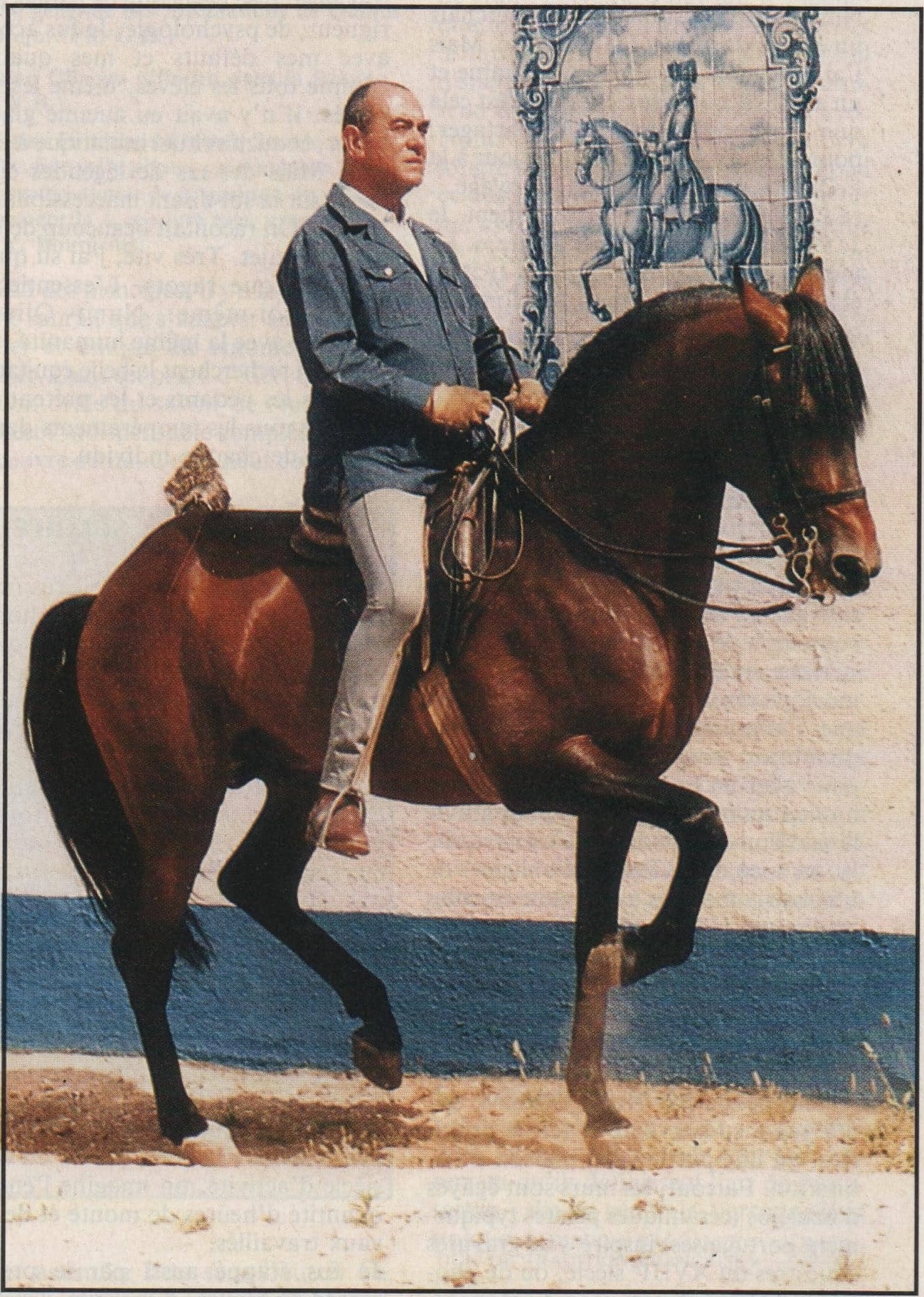

In the same way, under the tutelary shadow of the Athenian author, the equestrian history of the West would have been constructed, surely penetrating the minds of those who agree with this theory, with this Greek miracle. The looseness of the hand, as well as the ethological knowledge and the different tones expounded by the Athenian author, would then constitute, as Michel Henriquet summarised, “the essential movements and postures that guided the first masters along the path of the high school of horsemanship” [78]. Similarly, the director of the Spanish School in Vienna, Colonel Podhasky, noted that the main figures of the equestrian art (piaffe, passage, levade) were evoked in the Xenophontic treatise, and taken up by the Viennese school [79].

Denis Bogros, squire of the Cadre Noir de Saumur, on the other hand, rejects any influence of Xenophon on the equestrian art of the Romans, from the Renaissance to the 19th century: “In the world of European chivalry, many things have been said and written about this master (430-355 BC) since the 19th century. Our historians have made him the inventor of horsemanship, and until recently he was the starting point of its history. That seems very exaggerated. Phidias had already decorated the Parthenon with his famous horsemen, while Xenophon had not yet climbed on a saddle.” [80] He made this obvious observation, moreover, that he had not yet been on a horse. 80] Moreover, he made this obvious observation, noting that the ancient author did not appear in most of the illustrious references in the treatises on equestrian art of the Renaissance and the modern period: “Even if we find it hard to believe, all this is very strange and makes us doubt the influence of Xenophon on classical equestrian art. For his influence on the French masters of the 19th century to be felt only belatedly, we have to wait for Dupaty de Clam, an illustrious Hellenist who translated the Greek master on his own account from the Greek manuscript, Paul-Louis Courrier [sic] and J.-B. Gail who published translations in our language. This matter worried too much the European historians of horsemanship, who, probably out of Eurocentrism, wanted a precursor from our continent” [81]. In general, M. A. Littauer, too, doubts a direct influence of Xenophon’s treatise on the theorists of the Renaissance and the modern period [82].

In fact, it is better to lean towards an intermediate option, between a reading that would validate a permanent influence of Xenophon on Western equestrian art, and a categorical rejection of any influence of the Athenian master until the 20th century.

Of course, it is not possible to accept the idea that Xenophon contributed all the principles governing classical horsemanship. The reins were different and Greek bridles were very demanding. It is in this context that his advice on the loose hand can be understood: the rider’s hand should not pull too hard on the reins, so as not to hurt the horse’s mouth [83]. Xenophon’s remarks on the importance of working the horse in the “bringing” and “gathering”, which equestrian theorists from Grisone to Berenger recommend [84], are common sense. Similarly, the advice of Cimon, on the need for gentleness in equestrian practice, taken up by Xenophon, does not validate the idea that these authors were developing ethological horsemanship in the modern sense of the term [85]. If ethological principles can be seen in Xenophon’s treatise, their reading is much more nuanced, as Xenophon writes that every refusal of the horse, considered as disobedience, results in punishment or additional constraint (VIII, 4; 13) [86].

However, as the books of Corte and Caracciolo attest, Xenophon’s teachings – on breeding, anatomy, as well as reins or equestrian figures – were spread from the Renaissance onwards, and indeed the posterity of these two books in Europe has not been denied. Xenophon’s influence can also be seen in the definition of the ideal horse. Indeed, it is possible that among others, Shakespeare may have read the first chapter of Xenophon to have written in his description of the horse of Adonis [87]

« Round-hoof’d, short-jointed, fetlocks shag and long,

Broad breast, full eye, small head, and nostril wide,

High crest, short ears, straight legs and passing strong,

Thin mane, thick tail, broad buttock, tender hide.” [88]

Therefore, the influence of Art équestre in Western Europe would merit a detailed study based on philological comparisons and an in-depth analysis of the contexts in which equestrian treatises or their different translations were written [89].

————————————

Voir ou revoir les interventions :

Colloque sur Xénophon, Paris 4 décembre 2019

« Le Traité d’art équestre de Xénophon : Modernité ou altérité ? »