Bartabas

We really enjoyed Bartabas' latest show, Irish Travellers, when we went to see it last December as a family - where all tastes are catered for. Not just for us, apparently, as it was extended until this spring (April 2). A few words exchanged with the artist, back in the warm cabaret where he was chatting after the show with a few friends, made us want to interview him. A solid interview, designed to say it all, to understand it all, to live up to the reputation of the master and the ambition of The World Horse Library, which is to serve as a reference whatever happens in the future. In short, it's an interview that takes time to prepare, and refers to the vast amount of existing documentation. And if you only knew how much ink Bartabas has spilled in his forty years on stage...

Journalists and writers have tried their hand at it. Dare we mention Homéric, Garcin, Nauleau, Gouraud...

We knew that the interested party was attentive to the written word. In preparing our questionnaire, we reread this statement at the start of a fine interview given to Marie Paillé in the summer of 2020 and published by L'Éperon: “I believe that the only beautiful words are written because you have been able to take the time to polish them, balance them, chisel them down to the last word: it's very similar to the work of a horse (...) Somewhere, having a beautiful sentence is like having a balanced horse”.

Armed with this certainty, we drew up a detailed, if perhaps a little tedious and lengthy, questionnaire and sent it to him, assuring him and his pen that there would be no limits.

The reply was friendly but unequivocal: “Dear Xavier

I've read your questionnaire, it's a novel! It's too long for me to answer... It requires a personal investment that I can't make at the moment!”. An honest answer, and one that is likely to make the sender question himself.

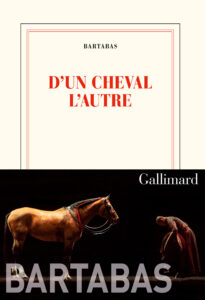

What if we were to go for the possible, which in the end would only be the essential? What if we took as our starting point the fact that Bartabas had already said a great deal, and above all written a great deal, in two books published by Gallimard in the prestigious Blanche collection?

We really liked D'un cheval, l'autre, published in early 2020 at the same time as Covid! We also read, later, twenty-six songs written during the pandemic, published by the same publisher, collected in an astonishing work entitled Les cantiques du Corbeau.

After all, yes, if we re-read what we loved and which basically answered some of our questions, particularly with regard to his sources of inspiration, his equestrian readings?

We were forced to conclude that, if the weight of words is anything to go by, the first trigger evoked in D'un cheval, l'autre is that of a photo he mentions on page 67, under the title of the “challenge” chapter devoted to the exceptional Quixote. “It's a very old photo, in black and white, it looks retouched. The horse and rider are clearly defined, but the bucolic landscape in which they are riding looks blurred and incomplete. (...) The caption: "James Fillis on Germinal galloping backwards. 1890.”

It is only in the wake of this visual emotion that allusions to fundamental readings appear throughout the pages.

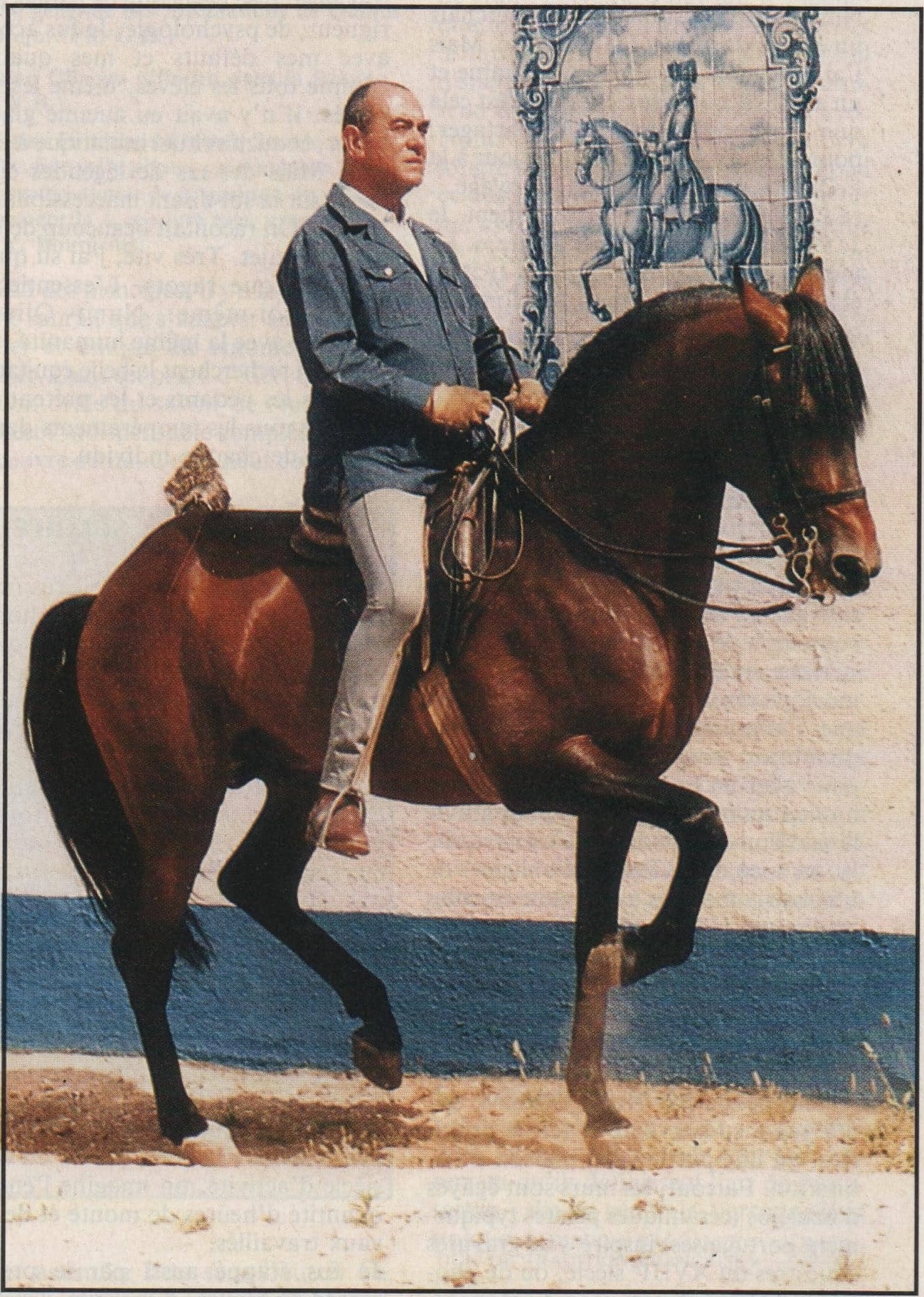

“The great figures of the equestrian art are my masters of insomnia. So much accumulated knowledge impresses me, from La Guérinière to Steinbrecht, from Pluvinel to Decarpentry, Licart,Franconi, Fillis, Raabe, Bragance, Oliveira, they guide my observation and force me to think”.

Of all of them, François Baucher “is the one who speaks to me, the one I listen to. His concerns are obvious to me; training and showing horses in the confined space of the arena implies a specific approach to their education. His 'second way' is my bedside book”.

A little further on, referring to Baucher, but also to other horsemen-writers and the relationships with the horses with which they practised their art, he expresses his astonishment: “Most of them boast of having trained them in record time, chaining them up like conquests, and only mentioning their names to associate them with their exploits. Oliveira, perhaps because he is the most contemporary, evokes these “sensations that have lifted his soul above the miseries of a human life”. In the letter accompanying Vallerine, his last mare, Étienne Beudant modestly hints, between the lines of his instructions for use, that training a horse is first and foremost a love story”.

Not only the written word, but also the image, when he evokes François Robichon de La Guérinière's indispensable École de Cavalerie, from which we can imagine that he had the privilege of consulting one of the two folios from the 18th century (1733 and 1751), which were illustrated by “Charles Parrocel - the second son of Joseph, known as the painter of battles - (who) is considered to be the best sketcher of equines in the kingdom. His father's training, combined with a spell in the cavalry, made him a master in the art of decomposing the gaits of a horse in motion”. The visual imprint of Parrocel's etchings led him to conclude: “having contemplated them so much, they have become tattooed on my imagination".

Of the equitation treatise itself, he confines himself to one observation: “the École de Cavalerie will become the bible of the defenders of traditional French equitation”, with a little further on in the same chapter, this understanding: “Horses' defences do not always come from nature... We often ask them to do things they are not capable of by trying to press them too hard and make them too knowledgeable”.

Once we'd done our reading, and in the absence of direct, easy answers to the questions posed for the dream interview, we had to look elsewhere. Poke around.

A portrait by default, in dotted lines, in hollows, as it were. It's the portrait of a character who has worked out his contours, who likes to portray himself through the little phrases and aphorisms he has sprinkled throughout his book.

At the end of each chapter, there are a number of well-chiselled little pastilles.

A collection that basically - and backwards - leads us to the questions that we had not been able to ask and therefore had not imagined.

About Zingaro? The theatre of a lifetime... The genesis:

“To build Zingaro, you have to think you can't be reduced,

You have to believe, want and dream,

And thus be born with a great deal of naivety

Like Don Quixote, I want the imaginary to be true”.

Is the intention, the dream that takes you away, that gets you going, enough?

“At Zingaro, when we create a show, we always start with the horse. It's a way of starting the adventure from the beginning”.

True, but what about the rest?

“To live Zingaro is to live relentlessly”.

“A life in which (...) men and horses move forward without understanding, without seeking to know”.

If you think about it, the life of a show troupe is “(...) a tribe in action. Beings reveal themselves in the very movement of their concrete lives”.

What about the troupe leader, dear Bartabas?

“At Zingaro, I sometimes feel surrounded by too many humans... Too much need for love”.

So why all the effort and pain?

“To defend your dream, the horses and the men who inhabit it, you have to live mentally in a state of perpetual war”.

A bit of respite though; somewhere?

“Horses don't demand anything of me.

Horses are my eyes for looking at the world”.

But what else?

“My horses have introduced me to men, and they have kept me away from them”.

Alone in the end?

“Riding a horse means sharing your solitude”.

So who are horses really?

“The masters to whom I submit my destiny.

They are my knowledge,

How can I pass it on, if not by appearing?

To understand it and work with it, I have to be me, ignore nothing and think with my buttocks”.

In return for what?

“By giving himself up body and soul, the horse offers me the key to my inner theatre”.

From which we can expect new and beautiful openings?

“Believe, want, dream.

The bells have rung too much.

The chimes are tired.

When will it end, when will I go home?

It's only so that I don't have to answer this question that I've never had a house”.

Why this insistence on something that never fails to appeal?

"In reality, I own nothing,

Neither land nor house.

The horses?

They own me”.

Disappointment at heart? Regret?

“Horses are carnivores, they've devoured my life and everything in it”

Realism?

“I walk at random.

I can hardly keep up.

I'm hitched to a dead horse”.

Damn! It's like an invitation to extend the subject. The future of the horse in a society that would disown it!

An appointment was made to talk about it. It was unvarnished. But probably too crude to be published here. Perhaps one day...

Xavier Libbrecht