Self-editing, an old recipe

The resumption of literary activities 2018 was shaken by the presence of a self-published book in the first selection of the prestigious Renaudot prize. This news unleashed the wrath of booksellers who have seen that option as a disturbing signal to the future of the book world. The profession fears content production that would be done without publisher and its diffusion without bookstores: this work, apart from being self-published, was disseminated in exclusive on an American online platform. The title disappeared from the second publication of the list, without it being known if the reason for the withdrawal was linked to the controversy or to the intrinsic quality of the writing.

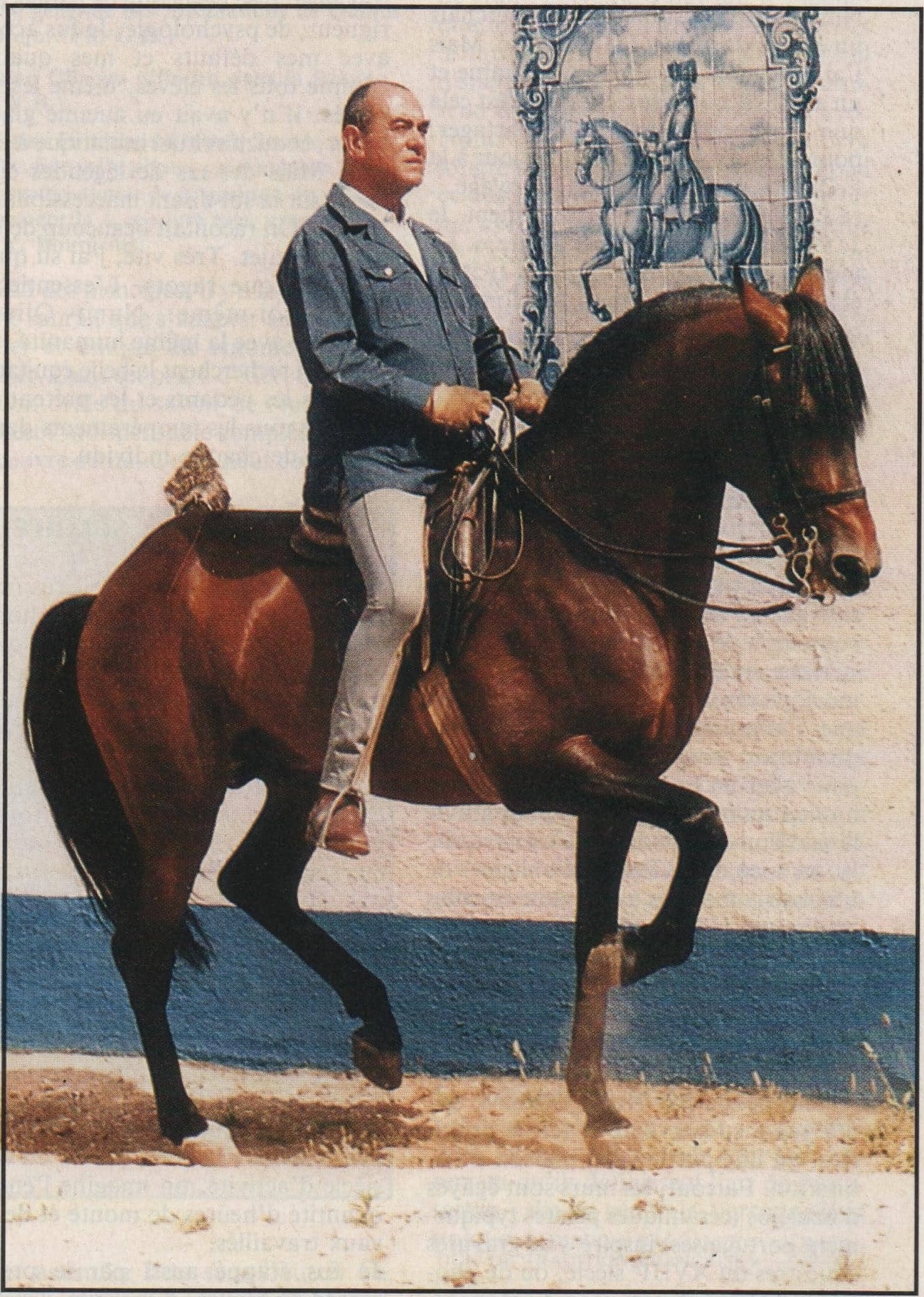

Self-editing did not always have such bad press. It was not unusual in the 19th century for an author to publish his texts himself. The horseman Francois Baucher might have even been the one who financed and guaranteed the dissemination of the second corrected and augmented version of his Dictionary (Paris, at the author’s, 1851). In this era, the number of publishers was not as extensive as it is now. In the case of this rider, the direct sale of books to his students was only more effective and profitable.

When the athlete, breeder, and lover of English horses, Charles-James Apperley, wanted to edit his book Nemrod, or the Race Horse Aficionado, (Paris, 1838), in French, he did it by his own means; his book could also be found in the Arthus Bertrand library; and the story stayed within a span of noses since the self-edited book for this English Lord is avidly pursued by collectors today.

See more: