Mennessier de La Lance, a man of horses and books

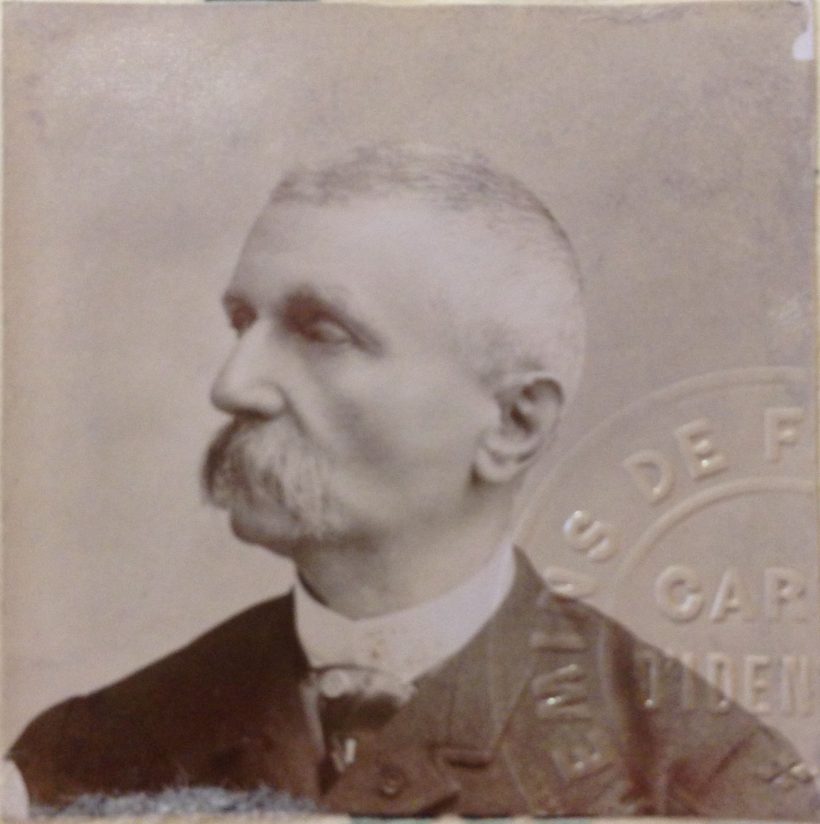

The first census of books in the World Horse Library is based on the latest authoritative inventory, published under the title Essai de Bibliographie Hippique (Paris, Lucien Dorbon, 1915-1921), which we owe to retired cavalry general Gabriel-René Mennessier de La Lance (1835-1924).

This bibliography took him more than 20 years to complete, and he continued his work despite the turmoil of the First World War. At a time when the internet did not exist, the valiant general travelled to libraries throughout France and Navarre, consulted booksellers, and wrote to collectors and archivists. He patiently and passionately read and compared each book listed. This colossal work catalogues more than 8,000 titles in French and Latin, most often accompanied by a biography of the author and insightful commentary on the text.

A veritable database ahead of its time

The World Horse Library follows the structure of this study, which proved to be perfectly suited to digitisation. Its alphabetical layout, cross-references in the text and classification tables made it easy to adapt to XML files. We were able to transform this paper book into a "database " while retaining its classification framework and content.

XML offers other reading and search advantages over the paper version: for example, the biography is accessible from each book record, the bibliography of a co-author or illustrator can be easily consulted, references in the text have been made dynamic (HTML link), searches can be restricted to a specific period or theme, and the digitised version of the title can be consulted if available, etc. It is also possible to return to the original content of the paper document at any time: by applying the “Mennessier” sort key from the ‘Advanced Search’ page, the complete corpus of the general can be found. It can then be saved, printed, etc. The addition of other bibliographies allows several sources of content to be concatenated, clearly distinguishing them on the same book record: for example, Mennessier's comments and those of Huth are clearly visible and dated.

The Essai de Bibliographie Hippique has thus become the cornerstone of a vast database of data. The task is likely to be a long one, as it is estimated that as many books, if not more, have been published since then.

While the focus at the time was on veterinary manuals and cavalry, today new themes have emerged that complement our equestrian knowledge: this animal was at the heart of our economic and cultural development before the automobile replaced it at the beginning of the 20th century. Nevertheless, the horse successfully navigated its revolution, moving from the military and agricultural worlds to become part of the world of leisure and sport. Mennessier de La Lance's efforts reveal a vivid snapshot of a world in the midst of change, which would accelerate after the First World War.

Continuing this inventory in his footsteps will undoubtedly shed light on new societal issues, helping us to understand how this rich and ancient companionship can evolve.

A motivated and privileged observer

The first volume of this important book was published in 1915, the second in 1917, and a final instalment in 1921. Probably frustrated at not being able to participate in the war to avenge the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine by Germany after the 1870-1871 war, and overtaken by age, this native of Metz decided to preserve the memory by developing a tool that he thought would be useful for his country. The 1921 supplement was honoured with a joint subscription from the Ministries of War and Agriculture.

Among the major themes covered, ranging from military and agricultural uses, horse riding, hippology, farriery, etc., the general was also interested in other published works, whether intended for the pleasure of the eye or for young people. Thus, his Essai covers no less than sixty themes.

It is noteworthy, however, that the majority of the works inventoried are books on care and breeding: this category includes 3,222 of the 8,065 works, of which 792 are veterinary manuals, 420 are devoted to equine science, 329 to equine medicine, 220 to anatomy, etc., representing nearly 40% of the total.

This was not the general's first attempt. He had previously published a 40-page brochure, not available in shops, on a conference on military tactics in 1892. His knowledge of cavalry regulations, both in France and in Europe, was an asset that he continued to cultivate through his reading. The shelves of his personal library must have been richly stocked. In fact, a manuscript by Bourgelat from his collection is kept at the École nationale vétérinaire d'Alfort.

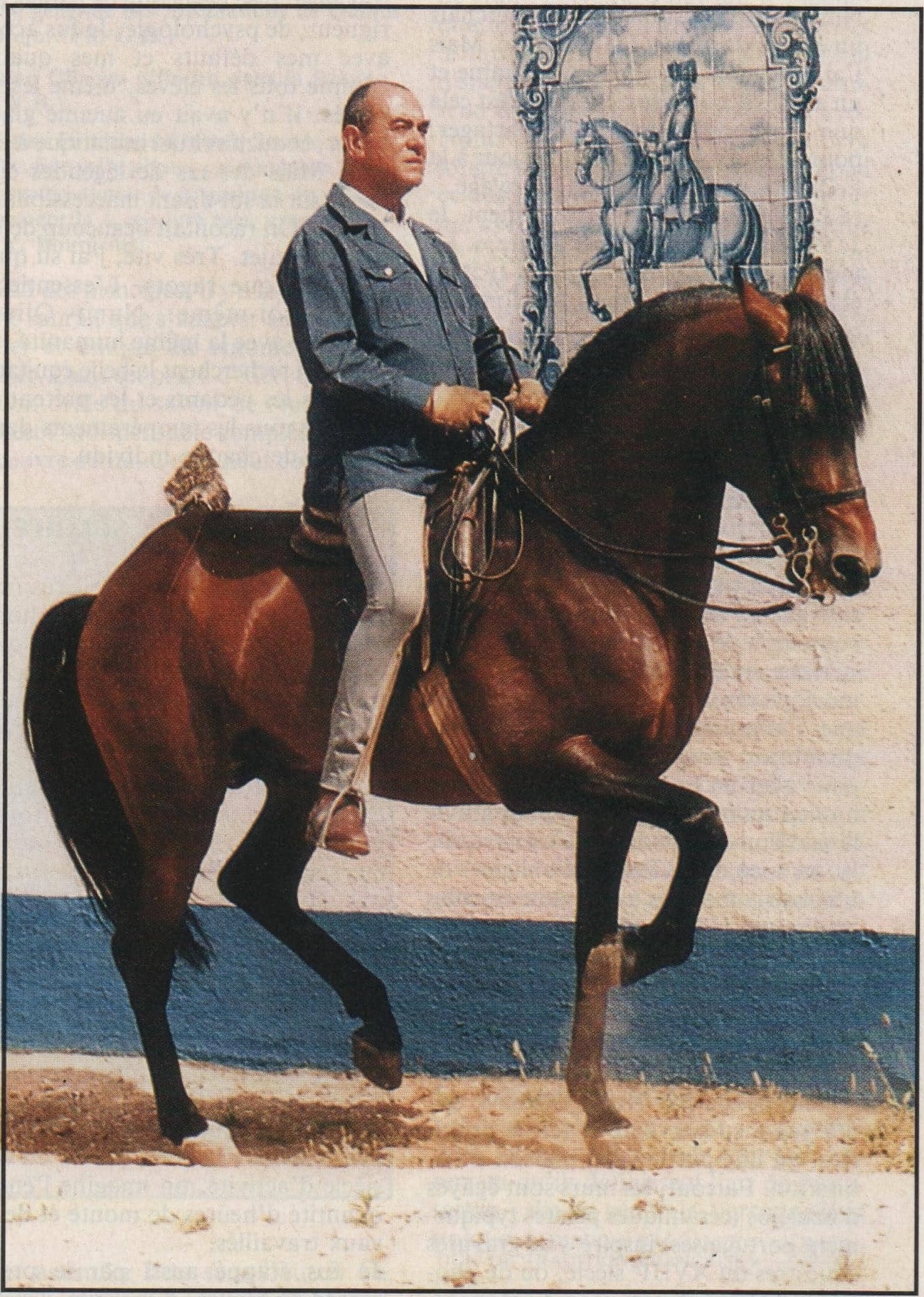

A keen observer of the equestrian world, Mennessier recounts the revolutionary importance of François Baucher's method, about which he patiently questioned his son, Henri. Did he also remember the teachings of the famous General L'Hotte, whose maxim “Calm, forward, straight” would become that of the Cadre Noir? We can assume so. Indeed, as a young soldier, Mennessier ‘served under his command for several years when he was a captain instructor in the 1stCuirassiers’, even though he found that his ‘cold and reserved character was detrimental to his teaching’. Mennessier attributed this reserve to the inner dilemma that L'Hotte must have experienced, torn between his admiration for Baucher and his method, which was banned by the War Ministry, and the loyalty he owed to his military corps.

Erudite commentator

Mennessier's verve reflects his habit of annotating military booklets. His comments are sometimes accurate and lucid, often impartial. He is not stingy with a few pithy sentences that are on a par with literary criticism: an empiricist's manual should ‘fall into the most fitting oblivion’, a short treatise on breeding is judged to be no more than ‘a modest average’, and a brochure is slammed as ‘not rising above honest mediocrity’. He does not mince his words when describing a method for learning to ride in an hour: ‘a very rare and very curious brochure, because it shows the degree of ineptitude that a man can reach when he talks about what he does not know and thinks he is an inventor’... The future readers knows where they stand!

Above all, he is a true enlightened witness of his time, who seems clear-sighted and aware of the changes taking place in the role of the horse with the advent of the railway and the motor car. For example, he pays tribute to the Delton photo studio because ‘this establishment has contributed greatly to the progress of the representation of the horse in art. Thanks to it, we have also been able to preserve the memory of many equestrian celebrities who are now gone and the brilliant teams of horses that the motor car will soon have rendered prehistoric.’ He was not far wrong... He was not fooled by the slow changes that the cavalry was undergoing. Not only did he analyse the regulations governing the organisation of this branch of the armed forces, which were sometimes completely unenforceable, but he also identified technical innovations such as the machine gun, which was responsible for great massacres during the First World War.

His father was a civil hospice administrator and also a painter. Mennessier probably owed his sense of proportion and his unerring eye for judging the faults and qualities of a horse to him. This was a talent he had to hone in order to judge the regiments' remounts. It can be found in all his notes on artists or in books containing engravings. His description can be damning if the drawing of the horse is too distorted, regardless of the artist's reputation. Rubens, for example, was given a dressing down for his engravings of l'Entrée de Ferdinand. Mennessier considered that “the musculature of his horses is completely fanciful, their hocks are deformed and the point of the hock is replaced by a flat surface like that of the knee; their fetlocks are even more deformed, etc., etc.” However, he tempers his judgement by describing the riders and accompanying figures as ‘superb’. The general is also very eloquent on the upheaval in the perception of galloping motion with the advent of chronophotography. He proves to be very knowledgeable about the experiments carried out by Marey and Muybridge.

A man of his time

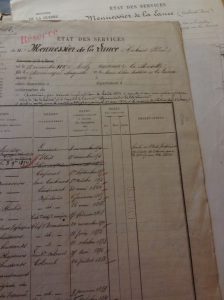

In Mennessier's day, you had to know how to ride or drive a carriage to get around. This tall, blue-eyed man, standing 1.80 metres tall, learned horse riding, fencing and swimming at the Imperial High School in Metz. He obtained two baccalaureates, in mathematics and literature, before continuing his studies at military school. He graduated in 1856 with excellent marks in hippology and a perfect knowledge of military regulations. However, his report card mentions that he was not very good at shooting. Never mind, that did not prevent him from rising through the ranks to become a major general in 1895. Although he spent much of his career in the Maghreb (nine campaigns in Algeria and one in Tunisia), he also saw action against Germany in 1870. His record of service remained impeccable throughout his 46 years of service.

His military file describes him as an elegant and vigorous horseman who rode extensively. This daily practice helped him to maintain a slim figure until his retirement in 1900 at the age of 65. It was from this period onwards that he devoted himself entirely to his bibliography, which he continued until he was overtaken by illness.

Almost nothing is known about his private life. There is no record of marriage or descendants in the civil registry. All that is known is that he lost his mother when he was a small child. His father then remarried his mother's older sister when he was 13 years old. Mennessier was granted the right to add his mother's maiden name, de La Lance, in 1858 by imperial decree.

Perception of the book

The first two volumes were published in the midst of the First World War, making their distribution uncertain. Nevertheless, they were well received across the Channel. William Osler, professor of veterinary medicine at Oxford, praised them in 1918 in a separate publication of the Veterinary Review, Vol. II, No. 1: "[...] The picture given in these volumes of the life and literature of our French brethren is very stimulating. The importance of the subject of equitation and training, and the various Systems are illustrated by the lives and works of Baucher, Aure, and others. In the bibliographical notes the complete story of the French veterinary profession may be read. The impression is left that this branch of our science is on a very high plane on the other side of the Channel. […]" William Osler, Bart., Regius Professor of Medicine, University of Oxford.

His book remains surprisingly relevant and still serves as an authority today.

His military file contains a touching letter requesting information from Ellen B. Wells, an American librarian and herself the author of an equestrian bibliography (Horsemanship: a bibliography of printed materials, New York, London, Garland, 1985).

The scope of the general's work goes beyond his initial intentions: his efforts reveal a vivid snapshot of a world in the midst of change. Horses were at the heart of our economic and cultural development before they were replaced by cars. If the animal has already achieved a revolution, moving from the military and agricultural world to become part of the world of leisure and sport, we can hope that it will still be there to face the ecological challenges that lie ahead. Perhaps the new inventory, undertaken by the World Horse Library, will provide some clues to help us see our current era more clearly.

Find out more:

- Mennessier de La Lance, Gabriel-René (1835-1924)

- His Essai (1915-1921)

- The books listed in the Essai de Bibliographie Hippique

Headlines bibliography cavalry old book portrait Commented Studies