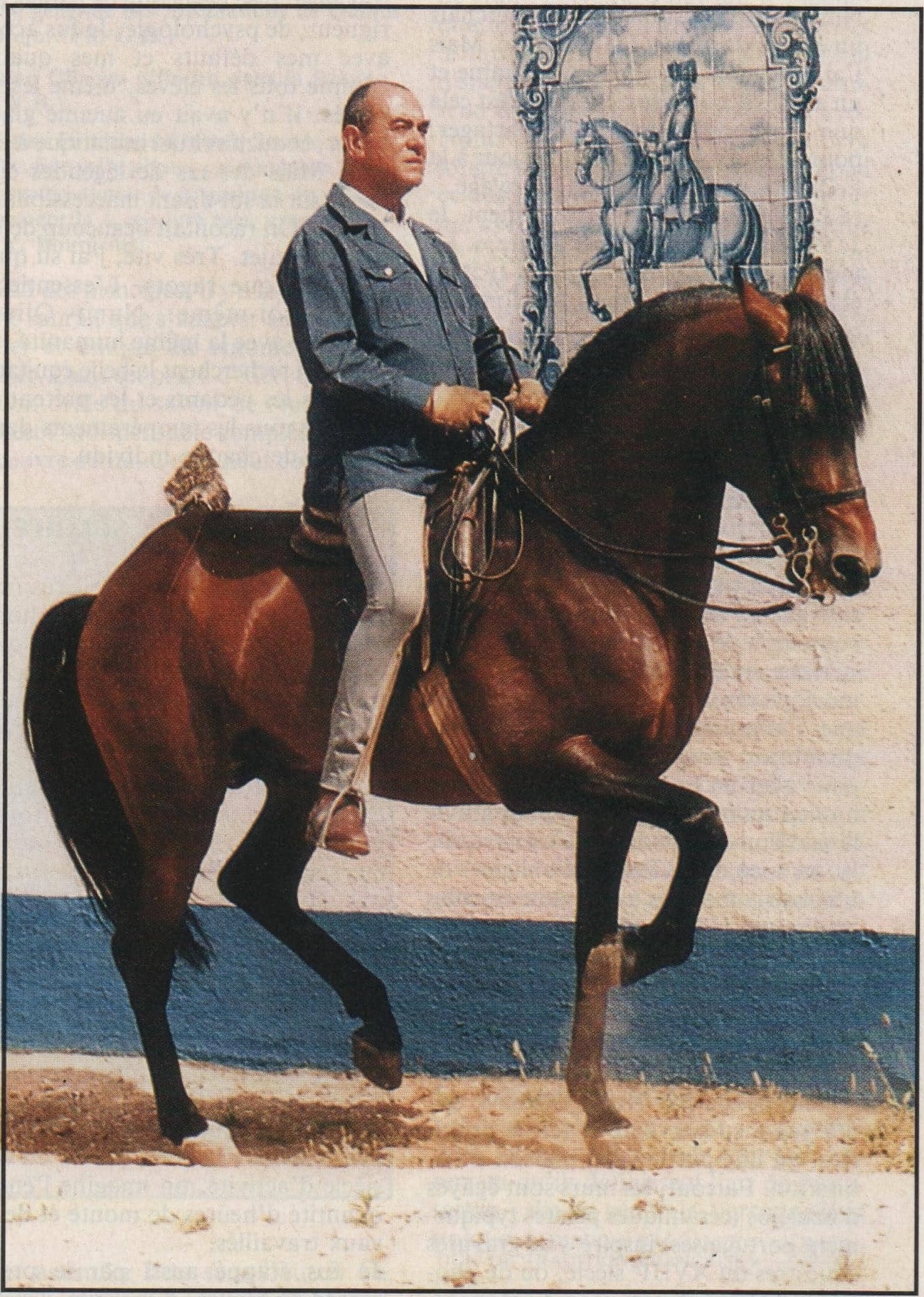

Mauro Checcoli in Federico Caprilli's saddle!

In 1964 in Tokyo, Mauro Checcoli won gold medals in the individual and team events in eventing on his horse Surbean. He also competed in the 1968 and 1984 Games, while pursuing a professional career as an architect.

From 1988 to 1996, he was president of the Italian Equestrian Federation (FISE). He still rides regularly, particularly at Pratoni del Vivaro, home to Italy's most prestigious eventing competitions, including the recent World Championships (2022). As passionate as ever, he has shown his interest in the development of the World Horse Library since its launch and, during the 2025 CSIO, which takes place on the famous Piazza di Siena in the heart of the Villa Borghese gardens in Rome, he organised a “special Italy” study day at the headquarters of the Italian National Olympic Committee (CONI) at the headquarters of the Italian National Olympic Committee (CONI), with motivated experts.

It was on this occasion that he introduced us to the unpublished work he prefaced with Marco di Paola, President of FISE, which was close to his heart and summarises all his equestrian experience and thinking, Federico Caprilli e la tradizione dell 'equitazione italiana, which is implicit throughout the interview he gave us.

X.L. - At the age of 21, you achieved the feat of winning two gold medals at the Olympic Games (Tokyo 1964), something that no one else, not even the gifted Mark Todd (double gold medallist in Los Angeles and Seoul), has ever achieved at such a young age. What memories do you have of this achievement?

M.C. - How do I feel about it today? Didn't I dream of being an Olympic champion? It was more than sixty years ago when I think about it: no Italian journalists, almost no television! Only my memory, a few newspaper articles, a few rare photos.

X.L. - Looking back, what was the most decisive factor?

M.C. - Several factors, of course, but above all the support and teaching of a great Italian equestrian maestro, Marquis Fabio Mangilli, who had trained the riders, selected the team and purchased the horses, which were young Irish thoroughbreds of very good quality. We all had a great passion for horses and had undergone more than two years of continuous training under the command and supervision of Fabio Mangilli, who demanded great discipline. In short, we were ready for this Olympic competition. Enthusiasm and a little luck too, perhaps.

X.L. - What was your horse like? Who was he? What was his character like? What were his abilities? Any anecdotes?

M.C. - Surbean (not to be confused with Sunbeam, ridden by d'Inzeo NDLA) was a grey thoroughbred, born in Ireland. He had a strong personality, which posed serious problems for the rider. He quickly gained confidence with me because, from the outset, whenever possible, I gave him the freedom to gallop when he asked for it. I accompanied him as much as possible in his actions, trying to avoid conflict.

He was a very good jumper, both in show jumping and cross-country, very respectful, never touching the bars and jumping very high. He needed to be treated with kindness and gentleness. A distinguished, elegant and energetic horse, he was also quite good at dressage.

When he arrived in Italy, the first few weeks of his training were difficult. He was almost wild and it was a real challenge for us, with no guarantee of success. As our training progressed, he was entrusted to me. I had undoubtedly won his trust and convinced our trainer that I was the right rider for him! I think we made a good match. Unique. Didn't the outcome of the Tokyo Games prove it?

X.L. – His dressage? His training?

M.C. - Patience, patience and more patience! And the keen eye and tremendous talent of Fabio Mangilli as a trainer. The result: Surbean performed quite well in dressage and was naturally the fastest horse at the end of the endurance event, whether in steeplechase or cross-country. He finally completed a flawless course in the show jumping event, which I remember being very difficult and which dashed the hopes of many competitors.

X.L. – Your talent?

M.C. - Dare I say it? I was a strong athlete, having practised athletics and basketball; I think I also had a certain amount of courage and, above all, a great love for this wonderful horse. In addition, I had the great patience mentioned above; I was very calm and, according to what people said, had a very good position in the saddle thanks to my successive riding instructors, all from Pinerolo and the Italian Cavalry School.

X.L. – Your character?

M.C. - Patient! Yes, I think calm and... rational.

X.L. – Your equestrian education? Your teachers?

M.C. - As I said, especially Marquis Mangilli, who gave me the strongest foundations and certainties. Before him, other excellent riders had given me valuable advice and precepts: Vittorio Zecchini, also a student of Mangilli; General Lequio, Olympic gold medallist in show jumping in Antwerp.

X.L. – Has the quality of teaching changed sixty years later? How? Why, in your opinion?

M.C. - Yes, the elimination of the Cavalry Regiments and the Pinerolo School were dramatically decisive in the process of transmitting what was admiringly called ‘Italian horsemanship’, represented until their departure from the international scene by the brothers Raimundo and Pierro d'Inzeo. Nothing has filled this void.

X.L. – Were you already reading treatises on horsemanship at your age and in your era?

M.C. - In my day, in the 1950s and 1960s, there were very few books on horsemanship available in our bookshops, particularly in Italian. It was later that I discovered the existence of books by great 19th-century French horsemen and writers.

X.L. - Which ones made an impression on you?

M.C. - Especially the writings of General l'Hotte, a contemporary of Federico Caprilli. And then, of course, the works of Caprilli himself and Colonel Alvisi, who established the connection between French and Italian horsemanship.

X.L. - Why do you think 16th-century Italian horsemen were among the first Europeans to pass on their knowledge in writing?

M.C. - Because, during that century in particular, they were the first to develop and record in books (thanks to the discovery of printing a century earlier) equestrian knowledge in the context of an explosion of all cultures: painting, architecture, sculpture, poetry, music, science, etc.

X.L. - How did they influence European equestrian culture?

M.C. - Modern dressage descends directly from these Italian masters (Russio, Pignatelli, Fiaschi, Grisone, Ferraro, Corte, Caracciolo, Pavari) who, through the renown of their teaching and their works, established schools throughout Europe, starting with France.

X.L. – More recently, and more specifically in the discipline of show jumping, it was another horseman, Federico Caprilli, who was a pioneer. Why does he inspire such admiration?

M.C. - Simply because Caprilli was a revolutionary genius who created a system based on a deep understanding of equine ethology. As a result, his horses and students were the fastest on all types of courses, while their horses were healthier and easier to train. From then on, all over the world, starting with his students at the Pinerolo School, riders followed Caprilli's concept of riding ‘forward’ and were all the better for it compared to those who did not evolve quickly enough. The revolution was swift.

X.L. – Are these writings, manuals and treatises on horsemanship really useful? How can the experience of the ‘great masters’ contribute to the training of a rider?

M.C. - They are essential for providing the cultural and technical foundation for all amateurs and especially professionals (competitors and trainers) who want to know the fundamentals of riding, which are valid in all circumstances.

X.L. – You were President of the Italian Equestrian Sports Federation. What were your observations on this subject? What initiatives did you take at the time?

M.C. - Thirty years ago, I tried, through the FISE, to revive the culture and tradition, in short, the equestrian heritage of Pinerolo, which the government of the time had sadly interrupted! During my term of office, the Federation organised training courses and issued regulations to improve the quality of teaching in Italian clubs. The courses were led by teachers from Pinerolo and high-level competitions were organised to promote this revival. After I left, all this was forgotten and abandoned. Only in recent years has the Italian Equestrian Federation opened new facilities in Pratoni del Vivaro (near Rome, editor's note) with ongoing training for riding instructors. I myself am the technical manager of this revival, and we now have to wait a few years to ensure that the training of these young professionals yields the expected results.

X.L. - And today? What could be done to pass on this knowledge and expertise to riders?

M.C. - We must continue to build on the legacy, the wealth of knowledge and experience of Pinerolo and Saumur. The world's most successful riders, on both sides of the Atlantic, follow the precepts of Franco-Italian technical culture.

X.L. – Tell us about your personal library. What are your favourite books? Your favourites?

M.C. - My favourite books are a mix of authors from Pinerolo, such as Alvisi, Santini, Mangilli, and many French authors such as L'Hotte, Benoist-Gironière, General Pierre Durand and, more recently, Michel Robert. I also refer to the Dutch author Paalman, the German author Klimke, the Russian author Rodzanko and many other American authors whose works are inspired by those of Caprilli.

X.L. - You have supported La Bibliothèque Mondiale du Cheval since its launch, notably by organising a symposium in Rome in 2022 with CONI and FISE. What comments or suggestions would you make to improve its development?

M.C. - The World Library has become a unique and indispensable institution. The greatest professionals (riders and trainers) are not necessarily writers. They are actors in the saddle and on the stage and do not necessarily have the time to devote to training such as that enjoyed by their 19th-century predecessors. They take concrete action every day. Fortunately, things are done well. The most successful riders are also those who respect the welfare of the horse, which is itself considered by the general public to be the main ‘protagonist’ of our very special sport. The others, those who ignore the beautiful nature of the horse and do not care about it, do not obtain the same "commitment ‘ or the same “participation” from their mounts in their quest for performance.

This fundamental concept was established as early as the end of the 19th century by General L'Hotte and Captain Caprilli. These two eminent figures gave absolute priority to the ’nature" of the horse and respect for it.

Interview by Xavier Libbrecht