When the history of the Norman cavalry is really embroidered...

Interview with Pierre Bouet, Honorary Lecturer and Honorary Director of the Office Universitaire d'Études Normandes.

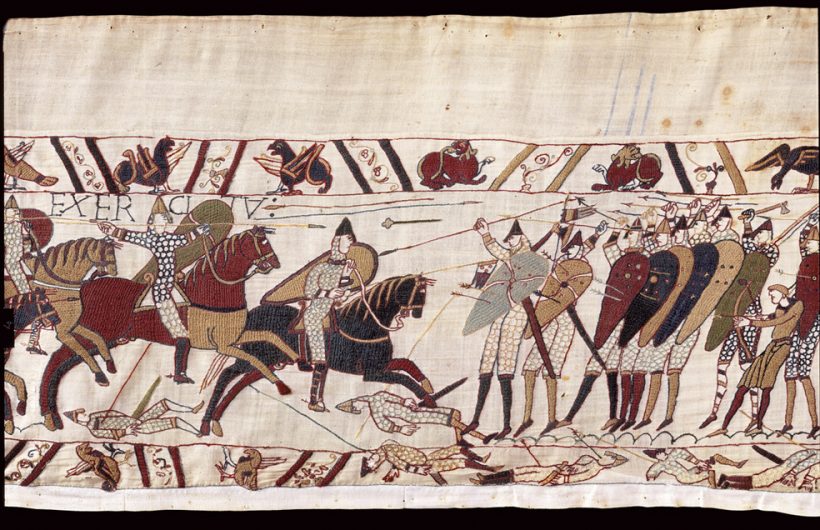

It is quite a story, that of the conquest of England by William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy, between 1064 and 1066. And that story is certainly well and truly embroidered, over 70 meters long and half a meter high, like the sound of an epic tale that can be heard... It's almost like a film roll. And in colour, please, for each of the 600 characters drawn out with strands of wool, which it would be a mistake to think that they all look the same. Nor do the 200 horses that animate it throughout the 58 scenes lying on 9 long pieces of linen sewn together.

The Bayeux Tapestry has been evoking, intriguing, moving and fascinating for almost a thousand years! For a thousand years, it has been a witness of Normandy's fabulous past. A thousand years which, with the pangs of age, require a restoration that should begin in 2024 and last eighteen months. Would such pause be likely to diminish the interest, by then, of the 400,000 annual visitors to the Bayeux Museum where it is exhibited?

Not at all! Since 2017, the Heritage Factory in Normandy, has taken photographs on the work outside its showcase, and the know-how of the teams from the University of Caen Normandy, Ensicaen and the CNRS, the collection is now available digitally on both on-site tablets and remotely on computers. This development not only facilitates the viewing and reading of the entire work, but also allows for scene-by-scene exploration and, thanks to a zoom function in maximum focus, the revelation of the smallest details of the embroidered motifs, all accompanied by a side information panel offering the translation of the Latin inscriptions into French and English.

Such a tool could have certainly facilitated, if it had existed at the time, the work of Pierre Bouet, a French academic, a specialist in Latin-speaking Norman and Anglo-Norman historians (10th and 12th Centuries), based in Caen, who devoted himself throughout his life to the study of tapestry to the point of being today, the undisputed specialist on the subject, as Tanneguy de Sainte Marie, former technical director of the Haras du Pin, kindly pointed out to us.

Suffice to say that when new took an interest in the horses that made up La Tapisserie, in the equestrian scenes that animated it, we retained, with the authorization of the publisher of In Situ, the heritage review of the Ministry of Culture, only one source: the one signed by the current Honorary Lecturer and Honorary Director of the Office Universitaire d’Études Normandes. The Bayeux Tapestry https://journals.openedition.org/insitu/11967

Yes, it includes everything that has to do with the “horse” aspect.

All? Not quite. Horsemen curiosity is insatiable. They will ask questions about the origin of the horses, their breeding, the combat cavalry, their training, their excellence…

Therefore, we can’t thank Pierre Bouet enough for answering a few simple questions we asked him about the passion that drives a man for a lifetime; questions that also, perhaps, will get us to know him a little better.

(CR. Pierre Bouet, the guide to the history of The Bayeux Tapestry)

When was your first memory of the Bayeux Tapestry?

I visited the Bayeux Tapestry at the age of 12 in a school trip in 1950. I was a student in Caen, and I saw for the first time, during a school trip to Bayeux, both the Tapestry and the Cathedral.

What was your first impression?

I was more impressed by the story of William the Conqueror than by the iconographic masterpiece, which appeared to me to be very deteriorated. But I was surprised by the quality of the depictions of horses and ships.

Did it boost your imagination?

Yes, but it is mainly the story of William that I wanted to know: I devoted my entire life as a professor of Latin at the University of Caen to translating the Latin works written at the time to find out how the Normans had established themselves both in England and in southern Italy.

Is there a special detail you remember ?

Two details struck me on my first visit: the scene of the picnic of the Norman army and that of the death and burial of Edward the Confessor.

How much attention did you give to horses and riders then?

Being of rural origin and having participated in the harvests during my summer holidays, I was well acquainted with the horses that pulled the carts at that time; As a result, the presence of horses did not surprise me.

Didn't you think that at first glance they all looked the same?

No, they had already appeared to me to be different in their posture (stillness, trot, gallop) and, what is more surprising, in their different colours (yellow, green, blue, red...)

When, subsequently, did you become interested in this priceless embroidery again?

Very quickly I wanted to compare the account of the events recounted by the Latin texts with that presented by the Tapestry.

So?

Well, this is going to be a bit long! As I indicated above, I devoted my early years to studying the Latin historians who told the story of the Conquest of England: William of Poitiers who published around 1075 the “Gesta Guillemi ducis Normannorum et regis Anglorum” (Exploits of William Duke of Normandy and King of England), William of Jumièges who wrote the “Gesta Normannorum ducum” (Exploits of the Dukes of Normandy), and Gui of Amiens who composed a poem on “The Battle of Hastings”, Carmen de Hastingae Proelio. The comparison of their narrative with the Tapestry seemed indispensable to me.

As a result of this study I discovered a similar point of view between William of Poitiers and the Tapestry: the two works, traditionally described as pro-Norman, appeared to me to be of a real objectivity insofar as the character of Harold was recognized as a legitimate king since King Edward had designated him as his successor in articulo mortis “at the time of his death”. The study of the Latin text of these three works (including the reading of Orderic Vital) led me to consider that the Tapestry wanted, on the one hand, to present William of Normandy as a legitimate king and, on the other hand, to show that Harold had ascended the throne in accordance with the will of Edward the Confessor: it was Edward, the “reprehensible” character since he had changed his mind at the last moment. The Battle of Hastings thus appears to be a Judgment of God between two legitimate characters.

Tell us about your professional background?

I have devoted forty years of my life as professor of Latin at the University of Caen to the history of Normandy, from the Viking Rollo to the reconquest of Normandy by Philip Augustus in 1204: three centuries of history of the Normans who were active throughout Europe.

>Of your attachment to Normandy?

Originally from Normandy, I have made a point of learning about the history of my region, but the history of the Normans in the Middle Ages has never encouraged me to be chauvinistic. I have often even opposed associations that advocated a return to Norman or Viking origins and that did so without any real scientific objectivity.

So, what led you to take a more “scientific” interest in this embroidery, to study it?

The period 1064-1066 was decisive in the history of Normandy and England: this is what is depicted on the Tapestry. I was led to scrutinize it very closely, with my knowledge of the Latin texts that talked about this period.

When did you start? How long did this work take you? What were the steps? The pitfalls? The satisfactions?

1st stage: I started to work by studying the history of the Middle Ages, since, as a Latinist, my historical period of reference was Greco-Roman antiquity: I even wanted to follow the courses of my historian colleagues of the Middle Ages, Professors Michel de Boüard and Lucien Musset, who enjoyed a worldwide reputation and who had encouraged me to devote myself to the Latin texts of medieval Normandy.

2nd stage: I spent several years translating all the Latin texts from this period, some of which had never been translated into French or English. It took me 5-6 years.

3rd stage: given the important scientific production (especially in English) relating to the history of Normandy and the Bayeux Tapestry, I began to follow international conferences and meetings and to write papers.

4th stage: I was put in charge of a cycle dedicated to medieval Normandy at the International Cultural Center of Cerisy, and decided to organize a 5-day symposium on the Bayeux Tapestry by inviting all renowned researchers (American, Canadian, English, German and French): this conference allowed for a renewal of research and resulted in a publication in French and English in 2004, which still serves as a reference today.

5th stage: the dynamic created by this conference and the personal relationships between researchers have led to new meetings in England and France and opened up new lines of research.

6th stage: we are looking at the creation of a new museum in Bayeux (scheduled for 2026) with the active participation of all French and foreign researchers, who have been working together for more than twenty years.

The dissemination and reception of your work among and for specialists (academics, historians, etc.)? and for the general public?

I have written numerous articles on the Bayeux Tapestry, organized the 1999 conference (published in 2004) and collaborated in the organization of four other conferences:

- two in Bayeux:

“The Bayeux Tapestry, Chronicle of Viking Times” in 2007 (published in 2009);

“The Invention of the Bayeux Tapestry” in 2016, published in 2018;

- and two in England:

London British Museum: “The Bayeux Tapestry, New Approaches” in 2009

and Norwich: “Castles and the Anglo-Norman World”, 2012

For the general public, François Neveux and I have published a synthesis of all the research undertaken over the past century and a half in a very nicely illustrated volume:

“The Bayeux Tapestry, Revelations and Mysteries of Medieval Embroidery”, Ouest-France, 2013 (reissue 2017)

Satisfactions? Do you have any regrets throughout your career and your research?

A lot of satisfaction.

It is a pleasure to work on such a masterpiece and a pleasure to have initiated and contributed to the Tapestry specialists working together by defining common lines of research.

Regrets.

1) The Bayeux Tapestry is better known and better studied by the Anglo-Saxons than by the French. The reason is that the history of France is content to be a history of the kings of France (Ile de France), neglecting the exceptional successes of the regional principalities: Burgundy, Flanders, Brittany, Occitanie and ... Normandy.

2) The Normans themselves barely know the history of the Normans from the tenth to the thirteenth centuries with the conquest of England, southern Italy, Sicily and the Principality of Antioch. This is explained by an official program of the history of France that is silent on these subjects. In this, the Republic remained faithful to the sectarianism of the Capetian royalty.

At the end of the day, was what you learned at the end of this remarkable study far from what you may have imagined when you first encountered this work?

Yes, the result is very far from my first perceptions, which were “emotional”. Over the years of study and research, I have discovered that for three centuries Normandy has been exceptionally successful, to the point that Italian colleagues organized in Rome in 1994 a major exhibition on the theme “I Normanni, Popolo d'Europa”.

To this end, I participated in the organization of the exhibition and in the creation of a Center for European Studies on the Normans (Centro Europeo di Studi Normanni) whose headquarters are located in Ariano Irpino, near Salerno.

Interview by Xavier Libbrecht

Find out more about the horses of the Tapestry:

- Text by Pierre Bouet (In situ, Revue des patrimoines, 2015)

- The Books on Horses in the Tapestry

- The Norman Horse in the Middle Ages or (text version)

And to go further on the Tapestry and its digitization:

- The Bayeux Tapestry online

- The Tapestry's Spatialized Documentary Information System

- Documentarizing the Tapestry(Tabularia, 2018)