Patrizia Arquint, the Italian researcher behind her work

Patrizia Arquint (1955) is a well-known expert on Italian Renaissance manuscripts and equestrian works. But don't think she's claiming it. The extremely discreet Mrs. Arquint, holder of the Chair of Romance Philology at the University of Florence (prof. Lucia Lazzerini), doctor of research (Doctor Europaeus, XIX cycle) at the European Doctoral School of Romance Philology (University of Siena and consortium universities of Milan, Pavia, Paris IV-Sorbonne, Zurich, Santiago de Compostela) refuses to talk about herself and simply refers to her professional biography. No answer to a personal question; Not even a photo, a portrait.

To find out more, we had to look for a few testimonies that all confirm the researcher's concern for discretion. Giovanni Battista Tomassini, a journalist at Rai (for the parliament's channel), who also doesn't like to talk about himself, understands this demand. Passionate about Italian equestrian culture, he has published Le opere della cavalleria (Frascati, Cavour Libri, 2013, translated into English in 2014, The Italian Tradition of Equestrian Art , Xenophon Press) and states: “Although I never had the pleasure of meeting her in person, during my research, I was able to greatly appreciate her studies. She is one of the few Italian historians to rigorously apply a scientific approach in her work. It must be said that in Italy, due to a prejudice that is still hard to combat, the equestrian field has so far been little studied by cultural historians. Partly because most scholars mistakenly view it as confined to the dimension of “material culture”, that is, as an instrumental form of knowledge with little implication in other fields of knowledge. In part, too, because the study of ancient texts and documents on this subject presupposes a double competence on the part of the historian: that of historical research and that of specifically technical research in the equestrian field. Drawing on her training as a philologist and her passion for horses, Patrizia Arquint has always demonstrated in her studies a rigorous attention to historical sources and an ability to retrace documents and testimonies of great interest. I am thinking, for example, of her contribution to the few biographical sources concerning Federico Grisone, one of her works, concerning the equestrian field, that I appreciated the most.”

What can I add? Except that the World Horse Library can be honoured to have had the privilege of being able to interview Patrizia Arquint.

X. L.: We are partly familiar with your work on Italian equestrian literature and that's why we want to know a little more about you. First of all, is it the main part of your business? And, if not, what are your other areas of interest?

P. A.: Currently, I no longer consider myself working as a researcher. I'm in the process of putting together some of the work I've started and unfinished over the years, but I don't plan to publish it anytime soon.

X. L.: Is your university studies at the origin of this inclination towards the “equestrian matter”? Were you a rider? More generally, are you passionate about horses?

P. A.: After studying statistics and economics (I have a university degree in statistics and a bachelor's degree in economics and business, with a thesis on the history of economics), I obtained a bachelor's degree in literature (with a thesis in Italian philology) and a research doctorate in Romance philology. I've always loved horses, and for a while I also did a bit of horseback riding. So, I thought I'd apply my philological skills to the study of medieval and Renaissance books on veterinary science and horsemanship.

X. L.: Do you think you've covered the whole issue or do you think there are still surprises to come, texts, authors to discover?

P. A.: Even if we were to take into consideration only those works that we know but that have not yet been studied in depth, and even taking into account the fact that in recent years the number of researchers dealing with the subject has increased, studying in depth all this available material is already, in itself, a task that will take several generations of researchers.

X. L.: Is it correct to say that you have been more interested in the manuscripts — and therefore in the periods concerned — which are basically your specialty? What for?

P. A.: No, I don't make a distinction because I'm primarily interested in the texts. Since I have dealt with texts from the twelfth to the sixteenth centuries, these texts are sometimes transmitted in manuscript form, sometimes in printed form, and sometimes in both.

X. L.: Tell us about this wealth of Italian equestrian bibliography? Why is it important?

P. A.: From the point of view of the history of horsemanship, the history of veterinary medicine, and even history in general, Italian works show a quality that even we moderns are still able to perceive. As proof, we know that such quality was also recognized by the contemporaries of these authors and their works, and this is why they were so esteemed and sought out. From the point of view of the history of the Italian language, any text is important, especially if it is a text — such as those we are talking about — that was important in its time. In the eyes of the scholar, these works have the additional interest of having been little studied until now.

X. L.: More precisely, can you summarize it chronologically: authors and books?

P. A.: There are too many of them! And then, the work has already been done in the past: I will content myself with pointing out the most recent contribution: Le opere della cavalleria by Giovanni Battista Tomassini, which contains a precise bibliography and finally corrects several errors that, in the past, historians of veterinary medicine and horsemanship have transmitted without criticism.

X. L.: Physically, where are these works, knowing that the organization of public libraries in Italy has two so-called “National” points, Florence and Rome, and is in no way centralized, as for example in France under the BnF? Does this complicate your research?

P. A.: The works are physically where their individual events have led them, whether they have landed in a large library or in a distant convent. Dispersion is in the order of things.

X. L.: Were the authors of the first Italian equestrian manuscripts studied influenced by others: Arabic, Persian, Greek, etc.? Can you give some examples?

A.: For the time being, we can detect influences from Latin veterinary medicine (Vegetius, especially) and Byzantine (the Hippiatrica). As for Arabic, Persian, etc., the research remains to be done.

X. L.: In the fifteenth century, did the transition from manuscript to print play a role in the desire to pass on their knowledge on the part of the squires of the time?

P. A.: Those who had the desire to pass on their knowledge after the invention of the printing press used the printing press. Those who had a desire before, used the manuscript. The invention of the printing press obviously facilitated the dissemination of a work, but don't underestimate the speed and scale of transmission that a manuscript work — which was of interest to the public, of course — could achieve. We see it in literary works (Dante's Inferno , for example), but also in our field (Giordano Ruffo 's The Farriery, c. 1250), for example).

X. L.: Gutenberg (circa 1454)... What percentage of the population could read and write at the time? Who were the equestrian manuscripts for? The first printed equestrian books? Do we have an idea of the prints before and after Gutenberg?

P. A.: I can't answer the precise data on literacy and print runs, but I think there are studies on the subject. I can say that the Italian Middle Ages saw the early formation of a bourgeois social class which, needing it for its commerce, knew how to read and write, and I can also say that, given the liveliness of urban life, even among the lower classes, a certain literacy was possible. The addressees of equestrian treatises were people interested, by social obligation or profession, in a “cultured” use of the horse. The audience for farriery treatises was even larger, given that even the most modest horse represented value to the owner, and therefore had to be well cared for and specially if it fell ill.

X. L.: Was an illustrated manuscript more expensive to copy, rarer, than a printed book? Is it quantifiable? Do you have any examples?

P.A.: I'm not in a position to provide numbers (but again, I think experts in the field could provide them). However, I would like to take this opportunity to remind you that not all manuscripts are precious illuminated manuscripts. There are also rather shabby-looking manuscripts, copied by someone who was not a professional copyist but wanted to make a copy of a work he was interested in. Farriery treatises are often transmitted from these “poor” codices.

X. L.: In your opinion, are all equestrian and equestrian manuscripts scattered around the world (public libraries and private collections) now all listed? Studied?

P. A.: No.

X. L.: Has the diffusion and influence of equestrian manuscripts been studied throughout the Mediterranean basin?

P. A.: No.

X. L.: Italian equestrian is considered to have had its heyday at the beginning of the Renaissance. Do you consider, for example, as does Patrice Franchet d'Esperey, that Gianbatista Pignatelli (1525-1558), heir to the teachings of Frederico Grisone and Césare Fiaschi, established himself as the “transmitter” of Italian equestrian art to what would later be called, through La Broue and Pluvinel, “French horsemanship”?

P. A.: Italian horsemanship — with Naples as a centre of excellence — had its heyday in the sixteenth century (I avoid mentioning the Renaissance, because the temporal limits of this period are not unequivocally defined). In the second half of the sixteenth century, from the publication of the Gli ordini di cavalcare of Grisone , this equestrian culture poured into a happy series of manuals, almost all of which were the work of Neapolitan riders or those working in Naples. The transition of excellence that took place in the first decades of the seventeenth century between Italian and French horsemanship is a fact, and it is also a fact that there has been a transmission of equestrian knowledge from Italy to other nations. First of all, however, I would like to point out that it is misleading to juxtapose the names of Grisone and Fiaschi. Fiaschi , although author of a best-selling textbook, was never a professional rider and never taught. First and foremost, Fiaschi was a native of Ferrara and, although universally known and esteemed thanks to his textbook, he was a complete stranger to the Neapolitan environment. As for the Neapolitan milieu, we must not think of a school, of a tradition in some way unitary, but of a plurality of relevant individuals, of which Grisone was one, Pignatelli another, and many others also appreciated by horsemen. The fact that La Broue and Pluvinel , the first great French authors, studied in Naples with Pignatelli (and both were keen to make this known), might have led one to think that Pignatelli, in his time, was the most prominent personality, if not the only one. This is not true: he was an important figure, but not the only one (see the lists of Neapolitan horsemen in the works of Pasquale Caracciolo and the Ferraro father and son). There is also abundant contemporary evidence that in the sixteenth century, those outside Italy who wanted to perfect their horsemanship went to study in Italy, perhaps Naples, and those who, also outside Italy, wanted to hire a good rider, were looking for an Italian, or even Neapolitan, rider. Therefore, the transfer of knowledge between Italy and France cannot be described as having taken place between a few exceptional personalities — Pignatelli on the one hand, La Broue and Pluvinel on the other — in the space of a few years towards the end of the sixteenth century. The contact between the Italian and French circles was a much broader and deeper fact: many people, both students and professors, moved between the two countries for a long period of time — the whole of the sixteenth century at least.

X. L.: More precisely, we know of two manuscripts by Pignatelli, one on horseback riding and one on mouthpieces. Where are they? Are they accessible? One would be missing, on horseback riding, crucial according to experts: do you know where it is?

P. A.: I know a book by Pignatelli, L'Arte veterale , which is a treatise on veterinary medicine and which Mario Gennero and I edited. As I said at the time, I warn that the mention of Pignatelli is only in a secondary branch of the tradition and must therefore be taken with caution. As for Pignatelli's work on mouthpieces, I think it is the manuscript described in the Huzard catalogue at No.4380. Its current location is unknown, but from the few news items in the catalogue (dating, mention of other authors), it is clear that the actual presence and coherence of Pignatelli's material in the manuscript should be better clarified. For the time being, we know with certainty a type of mouthpiece designed by Pignatelli and described in Pirro Antonio Ferraro's Cavallo frenato and in other authors of the time. Finally, there is no known writing by Pignatelli on horseback riding, and there is no indication that it ever existed. If it ever appears, we'll celebrate!

X. L.: As we can see, we know it, the passion that drives you, whatever the object or the subject, is never satisfied! Is this the case for you in this area? What else would you like to seek?

P.A.: As I said at the beginning, I don't intend to undertake any new research.

X. L.: Is research a priori a solitary task? Easier as a team?

P. A.: I have always conducted my research, alone or in minimal teams.

X. L.: In this respect, can you tell us about your past collaboration with Mr. Mario Gennero? Do you still have projects together?

P. A.: The collaboration with Mario Gennero was very fruitful for me. The books we wrote together, as well as some that I signed alone, would never have been published without his commitment to finding publishers, etc. Having said that, and although - as I said - I have almost completely stopped my research activity, my experience in this area is still at the disposal of Mario Gennero.

X. L.: You have published a lot, can you tell us which books and studies you are most proud of? Why?

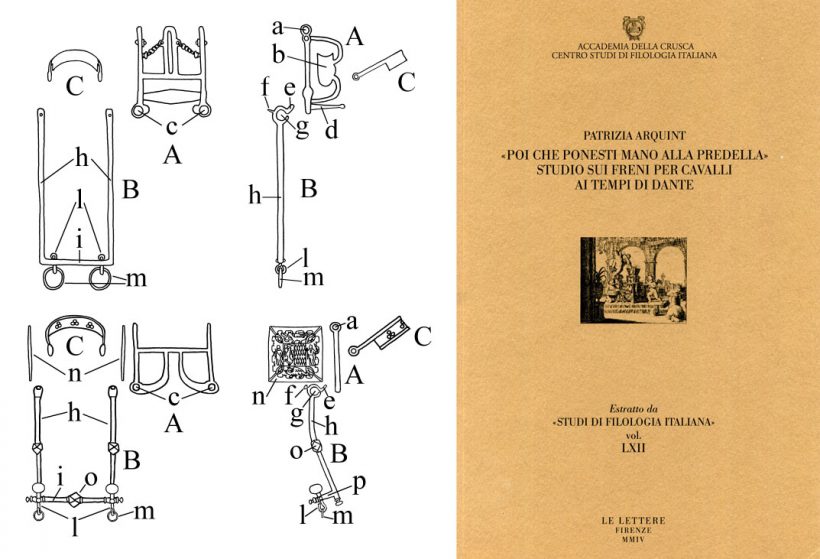

P. A.: An essay from 2004 Poi che ponesti mano alla predella (Study on the mouthpieces of horses in the time of Dante) “Studi di Filologia Italiana”, LXII, because it was original.

X. L.: Do you know the World Horse Library?

P. A.: Yes, of course.

X. L.: What expectations and criticisms could you make in order to make it more attractive, knowing that it has a dual ambition, to deepen knowledge on the one hand and therefore benefit from the credibility of experts and to transmit it to the widest possible audience?

P. A.: I don't know. But it seems to me that the project is a good one and that those who are in charge of it are perfectly competent.

Interview by Xavier Libbrecht