The certainty of an original treaty written by an unknown horseman

On 2 December, the MRSH in Caen will be hosting the second colloquium of La Bibliothèque Mondiale du Cheval, a project it has been developing for nearly four years.

The first, on the works of Xenophon presented by Alexandre Blaineau, was hosted by Hermès in Paris in December 2019. This was before the Covid 19 pandemic.

For a time, in 2020, it was envisaged that we would be able to organise the second edition of this event, which we hope will be held annually, in December in Caen, within the walls of the University, at the headquarters of the MRSH and La Bibliothèque Mondiale du Cheval...

In October 2020, we were forced to postpone the event.

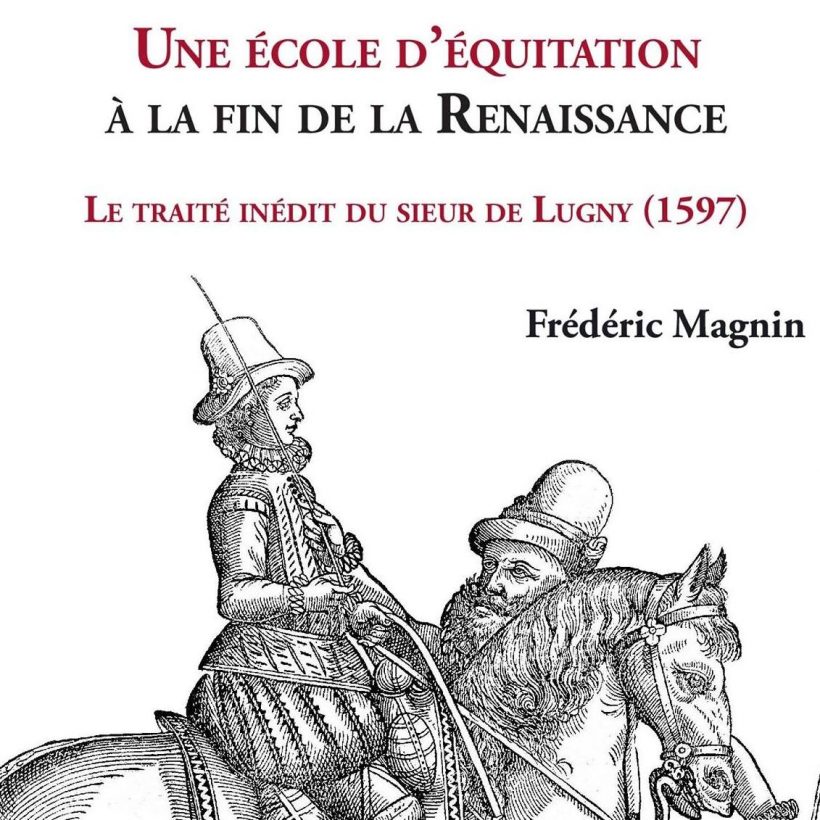

So here we are this time, with the theme envisaged from then on, which relates to the discovery of a hitherto unknown French equerry from the Renaissance, Louis de Chardon, Sieur de Lugny, author in 1597 of a manuscript treatise on horsemanship and hippiatrics “unearthed” by Frédéric Magnin, a researcher at the CNRS, who recently published a critical edition of this rare text, Une école d'équitation à la fin de la Renaissance, which he will be talking about on the morning of 2 December, assisted by Giovanni Battista Tomassini and Patrice Franchet d'Espèrey.

One question remains: who is Frédéric Magnin?

This is certainly not the first time the researcher has done this... And from the outset, in his answers to the questions in the interview that follows, he announces himself to be, to say the least, a little disconcerting: “My study model? Horned animals! Snails, whose calcareous shells are generally well preserved in sedimentary archives. These animals are symbolically the opposite of horses. They're crawling, close to the ground, indolent... but ambivalent par excellence!”

X.L.: You are a researcher at the CNRS in the capacity of “geomorphologist and ecologist, specialising in the history of Mediterranean environments”. Please tell us a little more about that.

F.M.: I've been working on the history of Mediterranean landscapes for around three million years, with a particular interest in the most recent period, since the last glacial maximum 20,000 years ago. The aim is to understand how temperate ecosystems were reconstituted during post-glacial warming, and to assess the role of human activities since the Neolithic period in the evolution of landscapes. My study model? Horned beasts! Snails, whose calcareous shells are generally well preserved in sedimentary archives. These animals are symbolically the opposite of horses. They are crawling, close to the ground, indolent... but ambivalent par excellence!”

X.L.: What about the horse? Why this quest? Do you ride horses?

F.M.: I was saying that the snail was an ambivalent animal. The proof: on horseback, we used to get noticed by performing caracols (literally snails) in front of princes, chiefs and ladies. If you look hard enough, you'll find a few links! But in fact my discovery of the horse came late and by chance. In my childhood and adolescence, horses meant the Camargue, Crin-Blanc, and the equestrian “ranches” that flourished in Provence, as well as a few references to the Cadre Noir. It was much later, while taking in horses on fallow land, that I first discovered horse riding, and then dressage. Just as books - old books in particular - have always accompanied my activities, they have also accompanied my equestrian apprenticeship.

X.L.: This isn't your first book... There was a previous one in 2006 devoted to Mottin de la Balme, subtitled “cavalier des deux mondes et de la liberté”, which won the Prix Pégase. What can you tell us about it?

F.M. : For Mottin de la Balme, it all started with his treatise published in 1773, Essais sur l'équitation, with its biting style, and also with what André Monteilhet had written about a man about whom almost nothing was known and whose trail was soon lost... So I set off in search of this “red gendarme”, from the village in the Dauphiné region where he was born in 1733, to the Illinois country where he died in 1780 while trying, on his own initiative, to retake Fort Detroit from the English. I wanted to analyse and describe in its entirety the extraordinary career of this brilliant squire, whose life would be worthy of a novel and a film adaptation. For me, his life and work were an opportunity to explore the social, cultural, military and, of course, equestrian history of the second half of the 18th century. In short, it was a wonderful adventure for the apprentice biographer and historian that I was! Augustin Mottin de la Balme hasn't had his own film yet... But we did pay tribute to him with an equestrian and musical show at the Château de Lunéville in 2006, in collaboration with Stéphane Béchy.

X.L.: In what way is “une école d'équitation à la fin de la Renaissance”, a critical edition of the “traité inédit du Sieur de Lugny”, different from this first work?

F.M.: Between Mottin and Lugny, there was also a foray into the nineteenth century with the translation of Henry de Bussigny's equitation treatise, published by Actes Sud under the title French Equitation. Un bauchériste en Amérique. The author was a somewhat enigmatic French squire who emigrated to the United States after the 1870 war. I owe the publication of this book, in 2013, to the confidence of Jean-Louis Gouraud, who let me have it! Aside from the interest of the treatise itself, this book was also an opportunity to investigate Bussigny and his compatriots, original in various ways, including Joseph Merklen and Joseph Baretto de Souza, all of whom came to teach riding school to the golden youth of Boston, New York and Cincinnati.

So let's dive into the Renaissance with Sieur de Lugny... Before discussing the differences, let's talk about what the three books have in common. In each case there is a chance discovery, unique and unknown characters, and works that provide opportunities to study horse riding from a variety of angles: the history of equestrian techniques, the social and cultural history of horse riding.. This book is different from its predecessors in that it is conceived first and foremost as a work of scholarship. I felt that this scientific approach was the best way to try and dust off the historiography of horse riding during these periods. There was a lot of recycling going on in this field! The basic material was also quite different, since the text was drawn up from several manuscripts with more or less significant variants. But in the end my method is always more or less the same, with a biographical component (reconstruction of the author's life) and a critical component (analysis of the work in context).

X.L.: When and why did this project begin to grow in your mind?

F.M.: The project began as soon as I discovered the first manuscript in an Oxford bookshop in 2013, and when I was certain that it was indeed an original treatise written by an unknown squire, Louis de Chardon, sieur de Lugny. It was then clear that I had to dig deeper and publish it.

X.L.: Without revealing everything that you will be revealing to us at the colloquium on 2 December at the MRSH of the University of Caen, could you tell us about the research process and method?

F.M.: I'm sorry I didn't take notes as I went along about the research process! At the outset there was a formidable challenge, with the only clues being the author's name (unknown), a regional affiliation (a gentleman from Touraine), a mysterious dedication to “gentlemen of the German nation” signed by the author in Orléans 1603, and finally, somewhere in the margin, the indication that the treatise was composed in 1597, that the author was forty years old at the time, and that he had been riding a horse for 25 years. You'll have to make do with that!

I think I started by trying to find information about the author, looking for the slightest trace, at the risk of following false leads. I then came across other manuscripts of the treatise - which were lying dormant in Danish and German libraries - and notarial deeds that had fortunately been dug up, and which led me first to Ferrara, at the court of Renée de France, then to Montargis, Saumur, Tours and Orléans. Not forgetting, of course, the author's fiefdom at Azay-Sur-Cher.

X.L.: Any doubts or disappointments?

F.M.: Doubts, certainly. All the time. I'm a doubter!

There were times when I wondered if I was on the right track (Mottin had taught me that there are lots of wrong tracks...). There were also times when I doubted the point of carrying out this enormous work.

X.L.: Any pleasant surprises?

F.M.: There have been some great moments of happiness, of course, the unmixed joy that every researcher experiences, at one time or another, when they discover something new. Even if the discovery is modest. The important thing is that it makes sense; that it brings understanding. The good surprises were the discovery of the first manuscript at the start of the investigation, then the successive discoveries of the other manuscripts, of the real identity of the author...

X.L.: What about outside help and encouragement?

F.M. : For years this work was totally solitary. Outside help came mainly from librarians and archivists, in France and abroad, and sometimes from historians who answered my very precise questions.

Encouragement and outside help came later, when I was confronted, as always, with the difficulties of publishing.

X.L.: At what point did you become certain that your research would result in the published work?

F.M.: Right from the start! Which was not the case for Mottin de la Balme. I published an initial article in 2014 in the Bibliothèque d'Humanisme et Renaissance journal in which I announced the future critical edition of Lugny's treatise.

X.L.: And how long did it take you to write the final version of the book?

F.M.: The work began in 2013 and was completed in 2018. Five years.

X.L.: And to publish it?

F.M.: The book was printed in 2019, so in the end it went fairly quickly. But after spending a lot of time and energy trying to convince publishers, to no avail.

X.L.: Was subscription the only option? What were the results in terms of print runs and sales?

F.M.: Yes, subscription was the only solution! It was during this final stage of the adventure that I received a lot of help and encouragement, especially from Patrice Franchet d'Espèrey, but also from François-Xavier Bigo. The material preparation and layout of the book were made possible thanks to the support of the IFCE and the association of Friends of the Cadre Noir.

200 copies of the book were printed. There is only one left, but a new print run of 50 copies is underway.

X.L.: Without betraying the essence of your contribution to the symposium, what does it add to our knowledge of the practice and development of horse riding in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries?

F.M. : Sieur de Lugny's treatise (in which there are a number of mood swings and recriminations), and of course the biography of its author, first of all give us a clearer picture of how equestrian teaching was carried out during this period. The role of the “riding academies” as a unique model has always been exaggerated. Lugny shows us a whole world of independent Italian and French equestrians engaged in fierce competition. What is also very interesting, and little known, is the role of the manuscript treatise in the spread of equestrian science and teaching in Europe. And then, of course, there is what Lugny has to say about the way in which pupils should be trained to become “riders” and teachers. Finally, there are also some interesting technical aspects. Lugny, for example, was the first to describe the “pillars” in their classic form.

X.L.: How will your talk be structured?

F.M. : As part of the World Horse Library, I'll be focusing on the astonishing itinerary of these manuscripts, which were probably written in Saumur but came mainly from Danish and German libraries. It's a complex journey, from the author's original intentions, which I'll try to decipher, to the plagiarisms, one of which was later published in a fine edition in Frankfurt in 1670.

There will also be a lot of talk about the author's biography, his profession as an equestrian, and all that this tells us about horsemanship at the time.

Finally, there will be two other contributions: Patrice Franchet d'Espèrey, who will give us his analysis of the technical aspects of the treatise, and Giovanni Battista Tomassini, who will shed light on French and Italian equitation through the treatise by Giovanni de Gamboa, a contemporary of Lugny and a pupil of Pignatelli. Tomassini has written a remarkable book on the history of riding in Italy, Le opere della cavalleria, which we would like to see translated into French.

Interview by Xavier Libbrecht